People find great satisfaction in labels: being able to refer to something as something, a type of something and a member of the set of somethings. Thus we find ourselves with the number google, the colour peacock, and identity crises over being a Millennial or a Zoomer. But when it comes to organisms, the need to label goes beyond the simple pleasure of adding a new name to the list. Once a species is named, it can be studied and assigned information. Distributions, behaviours, its place in the ecological community; a new piece of the ecological puzzle and a new page in the encyclopedia of common science. I have written before about a newly-discovered creature, the ‘shrine shrimp’ Jesogammarus acalceolus. I have also written on the tantalising prospect of an unrecorded echidna population in Australia’s remote Kimberley region. But I’ve since come across another unusual animal slinking around, in the ancient forests of Madagascar, and this one is a real brainspinner.

The ancient north-eastern forests of Madagascar play host to a mythical creature: a gracile black carnivore which slinks about the undergrowth. A feline, but larger and more sinuous than a housecat and only ever seen (fleetingly) beyond village borders. Long known to local people, the animal has caught the attention of ecologists and taxonomists who have borrowed a label from a local language and called it: the fitoaty. Work now turns to establishing what this thing is, how long it might have been there and how different it truly is from the household purring pussycat.

And, I’m afraid, this work is very much in its early stages. But I started writing this article, and I shall finish it, piecing together what I can from what little has so far been revealed…

Past

Some time 180 million years ago, the ancient continent of Gondwana was tearing apart. A mere 90 million years ago, the Indian continent finally separated from Madagascar. This, in brief, is how the island came to host some of the most unique ecological communities on Earth, minding its own business while much of the rest of the world was busy swapping lineages, mingling ecosystems and adulterating their endemism like some sort of smutty evolutionary orgy.

Madagascar is famous for hosting a boggling number of unique species – dog-faced lemurs, the world’s smallest bee, entire spiny forests. And the carnivorans are odd too: they belong to a wholly endemic family and have pub-quizzable common names like ‘vontsira’ and ‘falanouc’. No other members of the order Carnivora existed here, which makes the thoroughly catty fitoaty all the more puzzling.

Mariomassone | Wikimedia

Going back again, this time a piddly 11000 years ago, a wildcat of some kind was strutting about on a new island. This is not the Indian Ocean but rather the Mediterranean: Cyprus. Wildcats aren’t native here, and this individual is the first we know to have ever reached the place. Which means it is also the earliest record we have that they were brought here, and in fact the earliest record we have of any interaction between cats and people. We know about it thanks to a single phalanx discovered by archaeologists in 2012, who mention the word ‘cat’ only three times in their paper and announced this incredible finding in two short, understated sentences:

“Remains of cat (Felis lybica) demonstrate that this animal was already introduced from the mainland. This evidence predates any known interaction between cats and humans by 1,500 y.”

The point at which the domestic pussycat emerged from its wild ancestor is probably not a point at all but rather a hairy smudge. Some authorities, no less the IUCN, consider the domestic cat its very own species (Felis catus), with heritage lying in both the Eurasian (Felis sylvestris) and African (F. lybica) wildcats. I could write at great length about whether the distinction of an entire, wholly anthropogenic carnivore species designation is warranted or just a societal anomoly to make conservation policy easier but I’m frankly not yet armed to take on that argument. No matter how the labels are applied, though, things are going to get a bit confusing.

Present

Today, Madagascar has cats. Modern domestic cats are brought to the island as pets and pest control just as they are in most of the world, and usually left to roam just as they are in most of the world. But these pussies are not the first felines to set foot in the place. There are larger feral cats, more closely resembling true wildcats, dipping through disturbed habitat all over the island. These animals are always tabby-striped, measure around 60 centimentres long and show sexual dimorphism unseen in housecats, with males twice the weight of females. To avoid confusion, I’m going to adopt Sauther et al (2020)’s term ‘forest cat’ for these more feral chonksters. On their own, these are unusual creatures – descendents of domestic cats grown bulkier and adapted to a wilder existence in the unusual ecology of Madagascar – but there is something else. Something stranger, hiding in the rainforest shadows of the north-east, which is only just becoming revealed to science.

Another large cat has been anecdotally reported in the north-eastern rainforests around the Masoala Peninsula. In the Betsimisaraka Malagasy dialect it is called the ‘fitoaty’, meaning ‘seven livers’, and this name has been adopted by researchers. Legend has it that a man who accidentally snared one discovered seven livers inside the animal, thus the name, although local trappers take it only to be a story. I don’t know how Betsimisaraka Malagasy grammar works so I’m going to assume the plural of ‘fitoaty’ is ‘fitoaty’ and simpy hope that I’m right. Anyone in the know is welcome to either show me up as ignorant or congratulate me on my universal mastery of language.

Intrigued by the anecdotes, a researcher called Borgerson sought to confirm the creature’s existence and know it better by interviewing villagers in the region. The cat was said to be sleek, muscular and lean, weighing three or four kilograms, with a short, glossy black coat and, alarmingly, red-orange eyes. Out of 36 villages visited, people in 15 reported having seen the cat, though no more than 20% of any village’s population could make the claim. Except for one: a village singled out by Borgerson for more detailed interviews, where still only 22% of people had seen a fitoaty: always just one, usually running across a forest trail and never near a village. One neighbour even reported having chickens stolen from his remote forest home by a fitoaty, which would bring the poultry to its kittens waiting in a hole a full two metres up in a lalogno tree. You have to feel for a man who forfeited his fowl to a feline which scientists had yet to even discover.

Reports were tempting enough for a second team to head out with camera traps. They successfully captured images of a large, lithe Felis-looking cat with long front legs, a small head and all-black fur contrasting against pale eyes; while its eyes are disappointingly not a demonic red hue, the rest of the cat is still unlike any other on the island. And the strangeness surrounding the fitoaty doesn’t stop with its looks.

Farris et al 2015 Fig. 4

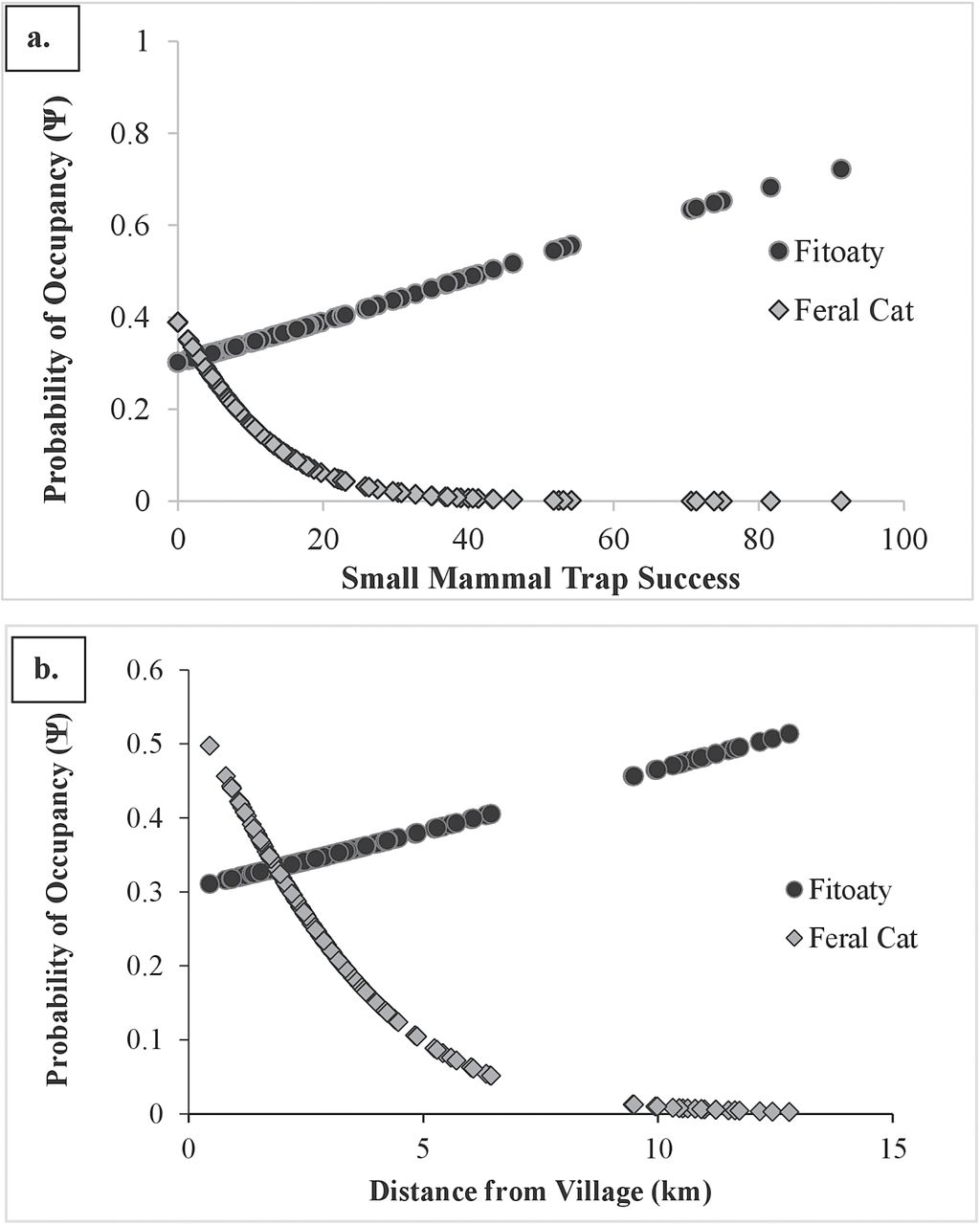

Recall that interviewees from that one village picked out by Borgerson said that fitoaty are never seen near the village. In Farris’ camera trap study around Makira National Park, fitoaty were actually recorded far more frequently that forest cats and seen in three sites where the tabby-coloureds were entirely absent. Fitoaty seemed to prefer less degraded forest sites compared to so-called forest cats of the area, avoiding both villages and forest edges. Farris et al’s statistics reveal even more evidence for contrasting ecologies between forest cats of the region and the even forest-ier fitoaty. Unfortunately, there’s no real way of saying this without it sounding a little technical, so: fitoaty occupancy (the pattern of occupied sites) was best explained by small mammal coincidence (recorded presence at the same sites), while detection (the likelihood of being caught on camera) went up with bird presence. Tabby forest cat occupancy was explained negatively by small bird and mammal presence, while detection correlated negatively with human coincidence. These contrasting patterns, fitoaty found more often in areas with small birds and mammals where the tabbies are rarer, suggests the two felines prefer different living conditions and might actually be avoiding each other. The lower detection rate of forest cats where more humans were recorded suggests they are also avoiding people, a pattern surprisingly not seen in the fitoaty: this is a point to those who consider the black cat to be an unremarkable population of regular feral kitties. But the researchers noticed a pattern smothered in the complexity of their models, and ran a new test just comparing likelihood of occupancy against distance from the nearest village. This time, forest cat presence fell quickly further from civilisation while fitoaty occupancy climbed.

Although a single camera survey of seven sites is less than decisive, it does suggest four important things: a) fitoaty exist; b) fitoaty prefer different habitats to forest cats; c) fitoaty prefer wilder environments away from people; and d) fitoaty are found more often where there are more small birds and mammals. Considering this, and the difference in morphology from forest cats, it really is beginning to seem like the slender, shadowy felines are something unique.

But this still doesn’t tell us what they they are. A genetic study on forest cats in other parts of Madagascar (the one that coined the term ‘forest cat’) concluded that they are likely descendents of domestic animals from the Arabian sea, possibly brought along early Arab trade routes hundreds, perhaps even a thousand, years ago. Unfortunately, the researchers only looked at cats from Bezà Mahafaly Special Reserve (3) and Ankarafantsika National Park (27), far from the north-eastern Masoala Peninsula where the slender, all-black fitoaty is found. If the more mysterious Masoalan moggie made it to Madagascar by the same means, why and how has it come to exist as a melanistic population with long legs and small heads? And why do they live away from their fellow feral felines? Either the fitoaty comes from some other source, perhaps a domestic breed unique to the region which as no household survivors, or they are of the same origin as the forest cats but have uniquely evolved traits to meet the pressures of their corner of the island. Or, and this thought is much more outlandish but all the more captivating, the fitoaty is some ancient lineage of cats which made its way to the island somehow long before any others, perhaps even before people made their homes there. Exciting as it would be to discover such a prehistoric lineage, the sensible parts of my brain insist that the other two explanations are the more likely.

Julie Pomerantz, Luke Dollar | Sokol 2020

Future

Just because it is unique does not mean it fits. Even if the fitoaty has been present in Madagascar for hundreds of years, it could be considered the same as any other invasive cat population and some day controlled for the sake of the native wildlife. The fitoaty occupies a far and wild corner of Madagascar, a nation unlikely to have resources spare for the mass control of an introduced predator right now; elimination of feral cats across an area as massive as Madagascar would take an incredible effort, and would probably start somewhere more accessible than the Masoala Peninsula, so the fitoaty might be safe for the time being. But I wouldn’t rule out an eventual programme to (rightly) protect the native species found in this corner of the world as Madagascar continues to develop. In a way, it would be a shame to see these unusual cats disappear, but so long as they aren’t some bizarre prehistorically-diverged animal, it’s better that the cats are controlled than we lose truly irreplacable naturally endemic species.

The long-term survival of the fitoaty may depend on its ecology, and whether or not it is harmful enough to remove. The challenge here is that the fitoaty has not been particularly studied and it’s unclear how much can be extrapolated from the habits of other feral cats. We know cats could eat their way through Madagascar’s native wildlife due to their adaptability, generalist hunting behaviour and ability to stalk elusively through the undergrowth; areas occupied by these adaptive predators retain lower numbers of rodents and birds, and they’ve even been observed predating lemurs (including, ironically, Lemur catta). They also compete with native predators: Farris (2017) found that, over a six-year period, occupancy by feral cats increased from nothing to 68% of camera traps, while four out of six native carnivores declined by at least 60% in the same space (though this wasn’t all the work of cats – invasive small Indian civets were also recorded and feral dogs are known from the area).

Remember that fitoaty were found more often where small mammals and birds were common. Certainly, the black cats are eating native species – they were even caught on camera with dead rodents in their mouths – so it is surprising to see this trend when feral cats elsewhere are known to be so invasive. One interpretation might be that fitoaty simply avoid villages, where mammals and birds are most scarce, and this is causing a false correlation, but this doesn’t explain why fitoaty numbers are high with small mammals elsewhere. Perhaps instead, the fitoaty is drawn to prey-rich areas and abandon anywhere where they have already slaughtered the local population. But this doesn’t seem like a complete answer either: fitoaty numbers would be highest where small mammals are slightly rarer because it takes time for predator density to build and the first arrivals would have already impacted prey numbers, which isn’t what we see – small mammal capture rates are actually higher with the highest fitoaty occupancy. So there is a hint that the black cats don’t have the same impacts as the other introduced felines, even if the info is only restricted to a single study relying on small animals passing camera traps. In typical fitoaty fashion, hints are all we get and there just isn’t a lot to go on yet.

Farris et al 2015 Fig. 3

If they were left where they are, fitoaties would presumably keep on adapting. Long legs and small head to navigate the understory, lean build for darting about and wrestling prey, black coat blending in with the forest shadows. They are among the largest mammalian predators left in Madagascar, only losing out to the famous fossa for top dog (or, this being Madagascar, top euplerid). Beyond this, it is too hard to say what might become of the fitoaty: maybe the population is sustainable, or maybe they are merely yet to kill off their prey.

Farris et al 2015

The fitoaty is an unusual and little-understood creature. Its origins are mostly unknown, as are its ecology, its invasiveness, its range and even its identity. What I am prepared to say with confidence is that this cat is weird, and well worth a better look. Because whether it is an ancient and unique lineage or an ex-domestic animal with a missing history, it is an unlikely creature to become mixed into one of the world’s most unusual ecological communities. And as it has made a home for itself in a land like no other, Madagascar has been transforming it into a cat like no other.

References

Borgerson C. 2013. The fitoaty: an unidentified carnivoran species from the Masoala peninsula of Madagascar, Madagascar Conservation & Development, 8(2), pp. 81-85 | Link

Farris ZJ, Boone HM, Karpanty S, Murphy A, Ratelolahy F, Andrianjakarivelo V, Kelly MJ. 2016. Feral cats and the fitoaty: first population assessment of the black forest cat in Madagascar’s rainforests, Journal of Mammology, 97(2), pp. 518-525 | Link

Farris ZJ, Kelly MJ, Karpanty S, Murphy A, Ratelolahy F, Andrianjakarivelo V & Holmes C. 2017. The times they are a changin’: Multi-year surveys reveal exotics replace native carnivores at a Madagascar rainforest site, Biological Conservation, 206, pp. 320-328 | Link

Gentry A, Clutton-Brock J & Groves CP. 2004. The naming of wild animal species and their domestic derivatives, Journal of Archaeological Science, 31, pp. 645-651 | Link

Hu Y, Hu S, Wang W, Wu X, Marshall FB, Chen X, Hou L & Wang C. 2013. Earliest evidence for commensal processes of cat domestication, PNAS, 111(1), pp. 116-120 | Link

Kitchener AC, Breitenmoser-Würsten C, Eizirik E, Gentry A, Werdelin L, Wilting A, Yamaguchi N, Abramov AV, Christiansen P, Driscoll C, Duckworth JW, Johnson WE, Luo SJ, Meijaard E, O’Donaghue P, Sanderson J, Seymour K, Bruford M, Groves C, Hoffman M, Nowell K, Timmons Z & Tobe S. 2017. A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: the final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group, Cat News | Link

Reeves CV. 2018. The development of the East African margin during Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous times: a perspective from global tectonics, Petroleum Geoscience, 24(1), pp. 41-56 | Link

Sauther ML, Bertolini F, Dollar LJ, Pomerantz J, Alves PC, Gandolfi B, Kurushima JD, Mattucci F, Randi E, Rothschild MF, Cuozzo FP, Larsen RS, Moresco A, Lyons LA & Youssouf Jacky IA. 2020. Taxonomic identification of Madagascar’s free-ranging “forest cats”, Conservation Genetics, 21, pp. 443-451 | Link

Sokol J. 2020. Madagascar’s mysterious, murderous cats identified, Science, 367(6483), p. 1178 | Link

Torsvik TH, Tucker RD, Ashwal LD, Carter LM, Jamtveit B, Vidyadharan KT & Venkataramana P. 2002. Late Cretaceous India-Madagascar fit and timing of break-up related magmatism, Terra Nova, 12(5), pp. 220-224 | Link

Vigne J-D, Briois F, Zazzo A, Willcox G, Cucchi T, Thiébault S, Carrère I, Franel Y, Touquet R, Martin C, Moreau C, Comby C & Guilaine J. 2012. First wave of cultivators spread to Cyprus at least 10600 y ago, PNAS, 109 (22), pp. 8445-8449 | Link

I love this blog! It’s the best!

LikeLike