It is a safe assumption that these words are being read through a transparent layer of plastic, a family of synthetic materials invented less than two hundred years ago but now found in huge global abundance. Unleashing unfathomable amounts of a new material on the world has some interesting outcomes, such as the concentrations of rubbish swirling slowly around the centre of Earth’s oceans, most famously the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. A floating diffusion of trash sounds inhospitable, but the resourcefulness of living things should never be underestimated. From the plastic habitat is emerging a whole new class of ecological community, where coastal species find a floating home alongside natives of the open ocean. So strange is this situation that scientists have had to scramble for new words lest they be rendered mute by the linguistic vacuum. They landed on neopelagic and plastisphere.

Haram et al 2021 Fig 2c

Past

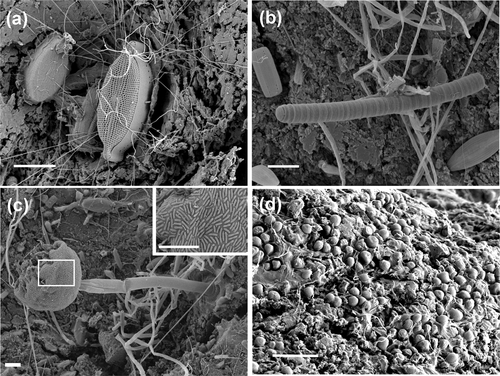

The ocean is big. Zoom into one part of it, the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre which revolves between the equator, South Asia and North America, and you’re still looking at one of the largest biomes on the planet. Its surface is also one of the harshest of our habitats, since consistent warmth from the near-equatorial sun prevents the upper layer from mixing with the rest of the water column, imposing a hostile low-nutrient ‘cap’ ruled by microorganisms. This is an isolated world of alphaproteobacteria, planktonic archaea and Prochlorococcus. Tiny zooplankton remove nutrients from this already starved ecosystem, feeding there at night but descending a kilometre each day, taking their organic matter with them and losing it to the depths through expiration, predation and defecation. Prochlorococcus, one of the most dominant microbe groups, also disappears from the surface, as much as half of the population dying off each day (mainly eaten by protozoa) only for the remaining half to go wild and repopulate, a ‘live fast, die young’ attitude.1

Luke Thompson from Chisolm Lab and Nikki Watson from Whitehead, MIT | Wikimedia

Within this microbe-managed microlayer exists a sparce animal community called the neuston, comprising things like snails, goose-barnacles, tiny isopods and buoyant jellyfish relatives (the floating pleuston), with crustaceans and young fish swimming just below (the hyponeuston). These are natural drifters, evolved for life on the high seas, and they are extreme specialists. But for as long as the Earth has had water it has also had rafts, a haphazard route for all kinds of species to cross the vast ocean desert and reach distant habitation. A route by which islands are populated, continents exchange species, and genes can flow between populations, it can spell great opportunity for those lucky enough to survive the trip. In fact, a recent paper suggests a dominant group of the world’s photosynthesisers were introduced to the open ocean by rafting on the chitinous exoskeletal remains of ancient Cambrian invertebrates like trilobites.

Yet, for all their significance across evolutionary history, these rafting events are usually fleeting and sporadic. It has always been thought that the surface of the open ocean is too hostile for most life, including coastal marine species, with its low nutrient supply, lack of shelter and high solar ultraviolet exposure. A change in maritime living conditions is changing this view, and a bizarre new habitat is emerging. It seems that some denizens of the sea can be surprisingly plastic in their habits.

Present

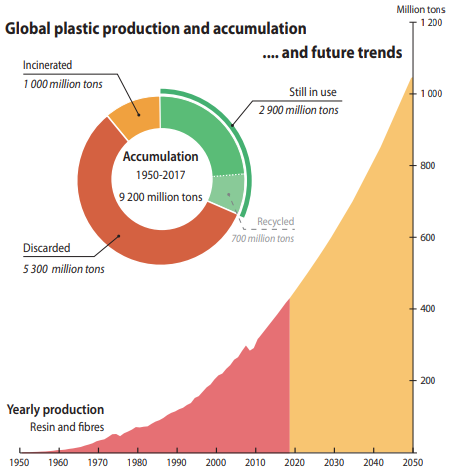

Between 1950 and 2017, some 9.2 billion tons of plastic were brought into the world, of which 7 billion became waste. Much of this has entered our oceans, with 75 to 199 million tons afloat currently, from miniscule threads which can be ingested and absorbed, to lost nets stretched across the seabed still catching quarry for no one, to great plasticbergs bobbing on the waves. It is widely acknowledged that plastic is bad, one of civilization’s guilty pleasures, but to face up to the extent of that badness is still eye-opening. A UN report handily provides a best-of list for its afflictions to the individual:

“entanglement, starvation, drowning, laceration of internal tissues, smothering and deprivation of oxygen and light, physiological stress, and toxological harm”

with an addendum that ingestion causes:

“changes in gene and protein expression, inflammation, disruption of feeding behaviour, decreases in growth, changes in brain development, and reduced filtration and respiration rates.”

Their effects on ocean ecosystems are similarly troubling, from reef damage to reduced sediment nutrient release to impacting primary producers and sending shocks through the entire global carbon cycle. And let’s not forget that plastic toxicity is concentrated up the food chain into those predatory fish, like tuna, that we so love to eat.

So, plastic is not good for living things. Except in one very bizarre instance where, at least at small scales, it is providing a new home to travelers of the sea.

Much of the ocean plastic floats and bobs across the ocean, eventually being pulled into one of the enormous circular subtropical currents that swivel in the middle of our oceans: the gyres. With no route out of orbit without degrading or sinking (both of which plastic is poor at), it accumulates into vast seas of flotsam. The fullest of these is the North Pacific subtropical gyre, containing over 79000 tons of debris spread across what has officially become the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. If the Seven Wonders of the World are matched by a list of the Seven Woes, this must surely be among them.

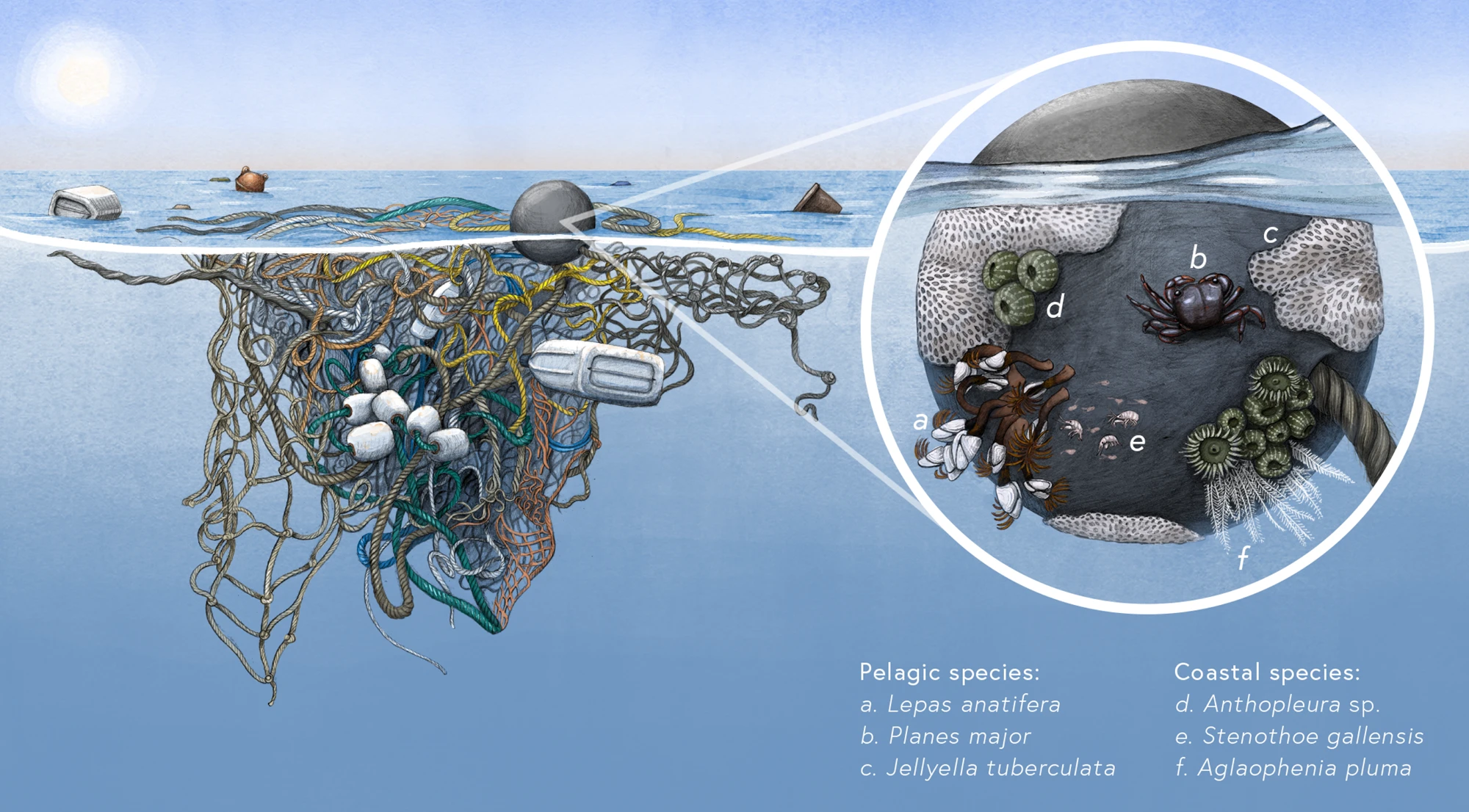

LeBreton et al 2018 fig. 3a

But for some species, all this litter presents an extraordinary opportunity. Plastics stick around, and the larger pieces presenting a stable substrate for species to attach to. This is not a common thing at the surface in the middle of the ocean: natural floats like logs break down quickly while dry land is absent by definition. Here is one of the few places on Earth where dirt and rocks are but legend, where the world is liquid and solidity is scarce; filling the subtropical gyre with plastic is like filling the Great Lakes with Loch Ness Monsters. What’s even stranger, though, is that these petrochemical islands are often occupied long before they reach the Patch: most of the plastic has been washed in from the coast where all manner of organisms have evolved to affix themselves to the shoreline. Those same organisms will make do with plastic litter, which may be washed out to sea and wind up in the wide, wide ocean, a long way from home. Here, the raft picks up oceanic lifeforms to create a bizarre blend of coastal and pelagic species, a mixed-up ecosystem never before seen in Earth’s history, dubbed the Neopelagic.

This community consists, by volume, mainly of oceanic species. Such wonders now associated with the implausible ecosystem include the skeleton shrimp Caprella andraea, a creature bearing a resemblance to a stick insect that’s been scrunched up and straightened out again, and Planes which is a kind of crab evolved to tuck itself into the nooks between a turtle and its shell5. Despite making up the bulk of the neopelagic fauna, surface-living and raft-clinging natives to the open ocean are rare and specialist, so by far the greater portion of the variety is made up of peregrine coastal species. Finding themselves in the middle of the sea, these have unexpectedly thrived in their new home, “common and diverse” according to a study which found that they made up 80% of the taxa associated with Garbage Patch plastic. Other abundant particulars include bryozoans, polycistines, anthazoa and diatoms7, 8, most of which are minute creatures forming crusts and films on their synthetic sanctuaries. The habitat may seem extreme but it has fostered an entire, complex system: most residents find their food by grazing across the plastic surface or filtering from the water, but others are detritivores working through waste and some are predatory hunters9.

Haram et al 2021 fig. 1

Plants are largely overlooked in studies, but fibrous algae also grow from the rubbish rafts7, further bolstering the lowest levels of the trophic web.

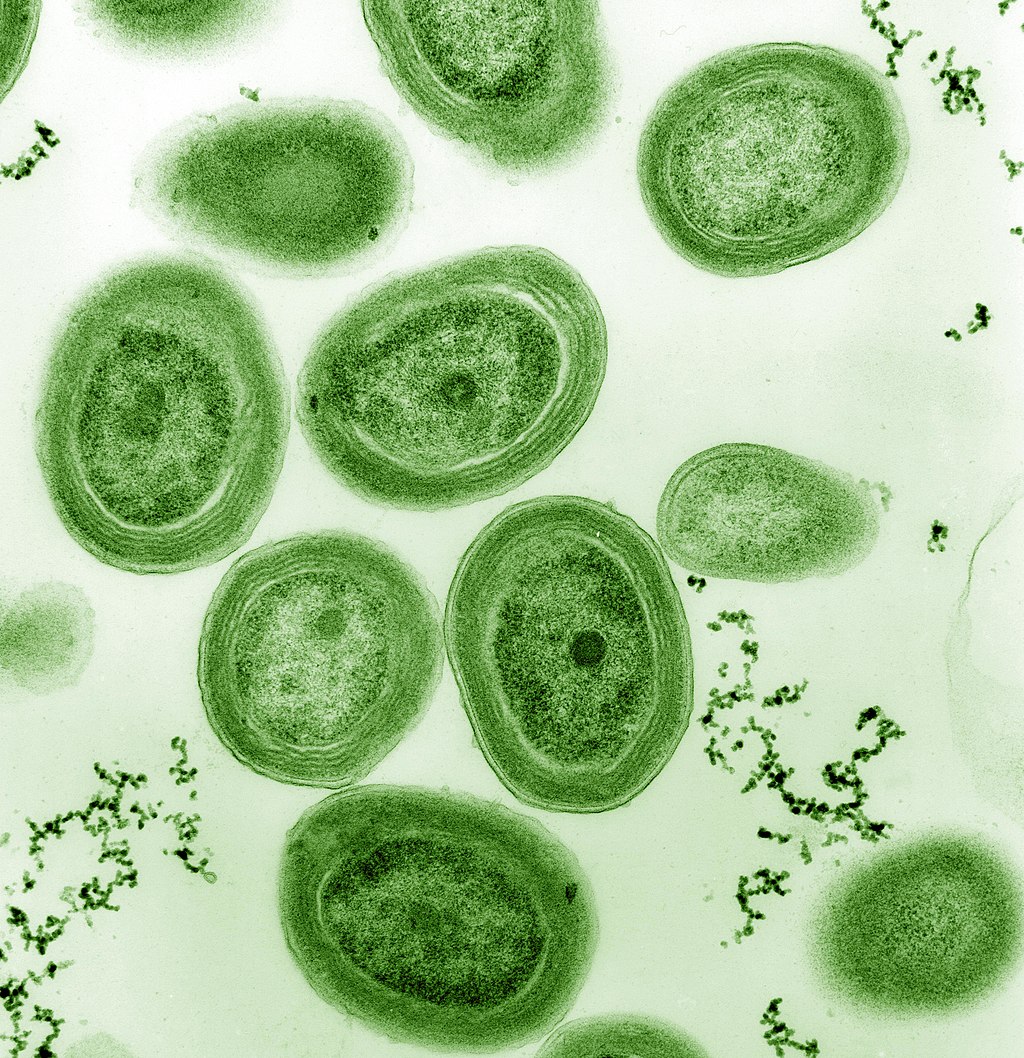

All of this richness is underpinned by the plastisphere, a vibrant microscopic microcosm quite different from the surrounding ocean. Most microbes here are adapted to life on a solid surface, with Bryozoa, cyanobacteria, alphaproteobacteria and bacteriodetes the main cast7; a similar collection of Latin and Greek were found to occupy plastics in the North Sea, with the addition of stramenopiles11. Paradoxically, the plastic litter provides a more nutrient-rich environment than the open water column by giving biofilms something to grow on and because nutrients dissolved in the water accumulate on the plastic surface, a curious phenomenon called the ZoBell Effect. More than that though, the microbial zoo swarming on the litter includes groups with plastic-digesting members13, and genes for the necessary enzymes were detected in the plastic-microbe soup7; the denizens of the plastisphere may be digesting their home, like a microscopic Hansel and Gretel in a kind of gingerbread houseboat.

Zettler et al 2013 fig. 2

As a brief but fascinating aside, the North Atlantic Subtropical Gyre (which, like the North Pacific and most oceans today, has its own growing garbage patch) has developed in recent years another kind of bizarre raft habitat, not of plastic but of seaweed. The Sargasso Sea is named for its masses of Sargassum, a brown surface-floating algae. For much of the last decade, the algae has enjoyed explosive summer blooms across the Sea’s southern and western edges, christened the Great Atlantic Sargassum Belt. Triggered by increased nutrient discharge from the Amazon basin and east Atlantic upwelling, these blooms are likely to be a recurring feature of the modern Atlantic thanks to fertiliser use, deforestation (increasing nutrient run-off) and climate change.

Future

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is full of living things swept away from their coastal homes far out to sea. Intuitively, they shouldn’t last long, but they have in fact flourished into a complex community. Since plastics famously fail to degrade, they provide a far more stable, persistent home not just for the wayfarers but for their descendants. Evidence of reproduction has been recorded in a range of organisms afloat for years after the 2011 tsunami swept them from the coast of Japan; some material was populated by short-lived coastal species nine years later. Incredibly, materials lost on the high seas (such as gear from fishing boats) have been colonised by ‘coastal’ species in the middle of the ocean, prospering on a piratical lifestyle! There are reasons to believe that Garbage Patch communities are able to rely on “resources generated by the rafting community itself”5, especially if carbon leaching from the plastics can be metabolised by plastisphere bacteria. It seems that the only thing stopping many of these seaside creatures living life on the waves in the first place wasn’t the extreme harshness of the big blue but the simple need of having somewhere to live.

The continued existence of the neopelagic is dependent on the supply of synthetic rafts. Small pieces with high surface areas tend to sink earlier, either due to faster degradation or a smaller buoyant mass counteracted by the amount of living stuff that can grow and weigh the piece down8, 15. Apart from sinking, plastic rafts are removed from the system by degradation through

sunlight, temperature, wave action and marine life, and by crashing into the odd coastline. Still, global plastic output is only increasing, with ocean litter tripling to 30 tons or so by 2040, or reaching a dizzying 53 million tons as soon as 2030, depending on which estimate you trust from a UN report. Thanks to established miscreant global warming, increased storm risk and severity further increase the rate at which litter of all kinds is snatched up by the ocean, especially given how close most of the world’s great population centres are to the coast. Plastic accumulation in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is exponential, with no sign of slowing, so its breadth will if anything grow in the coming years, or the gaps between rafts will shrink, providing only more habitat for seafarers. Higher sea surface temperatures and nitrogenous pollution will limit nutrient availability, but if the plastic itself really can support some freaky plastic-digesting microbes this might do little to slow the tide.

UN report ‘From Pollution to Solution’

I like to think that one day, non-plant-based plastics will go the way of asbestos, or CFCs, or the radioactive jockstrap. There are quiet noises about banning some of the more problematic forms of plastic in some countries but, without widespread uptake of a practical alternative, our world is likely to become only richer in petrochemical polymers. Bad news, objectively, for absolutely everything except the weird oceanic ecosystem depending on them for survival.

References

1Karl DM & Church MJ. 2017. Ecosystem Structure and Dynamics in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre: New Views of an Old Ocean, Ecosystems, 20, pp. 433–457 | Link

2PBS Eons. 2024. How Ancient Microbes Rode Bug Bits Out to Sea. YouTube | Link

3United Nations Environment Programme, From Pollution to Solution | Link

4Lebreton L, Slat B, Sainte-Rose B, Aitken J, Marthouse R, Hajbane S, Cunsolo S, Schwarz A, Levivier A, Noble K, Debeljak P, Maral H, Schoeneich-Argent R, Brambini R & Reisser J. 2018. Eviedence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic, Scientific Reports, 8, 4666 | Link

5Rech S, Bosco Gusmao J, Kiessling T, Hidalgo-Ruz V, Meerhoff E, Gatta-Rosemary M, Moore C, de Vine R & Thiel M. 2021. A desert in the ocean – Depauperate fouling communities on marine litter in the hyper-oligotrophic South Pacific Subtropical Gyre, Science of The Total Environment, 759, 143545 | Link

6Haram LE, Carlton JT, Centurioni L, Choong H, Cornwell B, Crowley M, Egger M, Hafner J, Hormann V, Lebreton L, Maximenko N, Megan McCuller, Murray C, Par J, Shcherbina A, Wright C & Ruiz GM. 2023. Extent and reproduction of coastal species on plastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre, Nature Ecology & Evolution, 7, pp. 687-697 | Link

7Bryant JA, Clemente TM, Viviani DA, Fong AA, Thomas KA, Kemp P, Karl DM, White AE & DeLong EF. 2016. Diversity and activity of communities inhabiting plastic debris in the North Pacific Gyre, mSystems, 1(3), e00024-16 | Link

8Zhao S, Zettler ER, Amaral-Zettler LA & Mincer TJ. 2021. Microbial carrying capacity and carbon biomass of plastic marine debris, The ISME Journal, 15, pp. 67-77 | Link

9Thiel M & Gutow L. 2005. The ecology of rafting in the marine environment. II. The rafting organisms and community, Oceanography and Marine Biology, 44, pp. 323-429 | Link

10Amaral-Zettler LA, Zettler ER & Mincer TJ. 2020. Ecology of the plastisphere, Nature Reviews Microbiology, 18, pp. 139-151 | Link

11Oberbeckmann S, Loeder MGJ, Gerdts G & Osborn M. 2014. Spatial and seasonal variation in diversity and structure of microbial biofilms on marine plastics in Northern European waters, FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 90(2), pp. 478-492 | Link

12Fletcher M. 1985. Effect of solid surfaces on the activity of attached bacteria. In: Savage DC, Fletcher M. (eds) Bacterial Adhesion. Springer, Boston, MA. | Link

13Zettler ER, Mincer TJ & Amaral-Zettler LA. 2013. Life in the “Plastisphere”: microbial communities on plastic marine debris, Environmental Science & Technology, 47(13), pp. 7137-7146 | Link

14Wang M, Hu C, Barnes BB, Mitchum G, Lapointe B & Montoya JP. 2019. The great Atlantic Sargassum belt, Science, 365(6448), pp. 83-87 | Link

15Carlton JT, Chapman JW, Geller JB, Miller JA, Carlton DA, McCuller MI, Treneman NC, Steves BP & Ruiz GM. 2017. Tsunami-driven rafting: Transoceanic species dispersal and implications for marine biogeography, Science, 357(6358), pp. 1402-1406 | Link

16Dotinga R. 2020. The lethal legacy of early 20th-century radiation quackery. The Washington Post | Link

17Rech S, Thiel M, Pichs YJB & García-Vazquez E. 2018. Travelling light: Fouling biota on macroplastics arriving on beaches of remote Rapa Nui (Easter Island) on the South Pacific Subtropical Gyre, Marine Pollution Bulletin, 137, pp. 119-128 | Link

18Carlton JT (Ed.) & Fowler AE (Ed.). 2018. Aquatic Invasions Special Issue: Transoceanic dispersal of marine life from Japan to North America and the Hawaiian Islands as a result of the Japanese earthquake and tsunami of 2011, 13(1). | Link

19Haram LE, Carlton JT, Centurioni L, Crowley M, Hafner J, Maximenko N, Clarke Murray C, Shcherbina AY, Hormann V, Wright C & Ruiz GM. 2021. Emergence of a neopelagic community through the establishment of coastal species on the high seas, Nature Communications, 12, 6885 | Link

20van Sebille E, England MW & Froyland G. 2012. Origin, dynamics and evolution of ocean garbage patches from observed surface drifters, Environmental Research Letters, 7(4), 044040 | Link

21Barnes DKA. 2002. Invasions by marine life on plastic debris, Nature, 416, pp. 808-809 | Link

22Ogonowski M, Motiei A, Ininbergs K, Hell E, Gerdes Z, Udekwu KI, Bacsik Z & Gorokhova E. 2018. Evidence for selective bacterial community structuring on microplastics, Environmental Microbiology, 20(8), pp. 2796-2808 | Link

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Le Qin for introducing me to the weirdly weedy Sargasso Sea