The Caribbean island of St Kitts is home to an unusual primate. With a typical pelage of floral shirts, loose shorts and open sandals, this animal can be found wandering aimlessly through the mountains or lounging on the sand. For much of the day, they may be seen clutching potent libations and falling into pickled dormancy. But tourists are not the only foreign mammals on the island with a taste for tipple: this is one of the few places on Earth where wild monkeys enjoy a boozy cocktail on the regular. Public drunkenness is not the only felony the green monkey commits in Saint Kitts though, and beneath the comical headline lies a complex and delicate situation for people, monkeys and native wildlife alike.

Charles J Sharp | Wikipedia

Past

Anyone who has woken up with a hangover and half-memories of the previous night’s poor decisions will recognise that alcoholic drinks aren’t especially good for the body. It seems bizarre, while the head thumps and the stomach turns, that people are drawn to the drink at all. When our senses have evolved to see, smell and taste toxicity in our foods, why don’t we all turn our noses up at stiff drinks? The ‘drunken monkey’ hypothesis posits that most animals with a diet rich in fruits and nectar must be equipped to deal with fermentation, and attraction to alcohol even serves to steer animals towards ripe food sources1. Ethanol, the alcohol produced in fermenting fruits, also stimulates appetite and may be linked to long life when taken in regular small doses1. Knowing the role fermentation plays in food preservation (think of kimchi or the watery rum partaken by pirates), perhaps alcohol also signalled that fallen fruit was still safe to eat. Our connection to such concoctions may have started because our ancestors came across more fermenting fruit on the forest floor when they descended from the trees: Carrigan et al (2014) identified a mutation in an alcohol-digesting enzyme from ten million years ago, around the time pre-human apes became less arboreal2. The excellent PBS show Eons has an episode on the human prehistory of fermentation which is well worth a watch. The plants also benefit from this arrangement: fermentation and microbial infestation makes fruit smellier and increases the chance of ingestion so that seeds are disperse3.

People certainly aren’t the only animals to enjoy alcohol. Chimpanzees in Guinea have been recorded using leaves as sponges to slurp fermented sap tapped from the raffia palm by humans4. The incredible bertam palm exudes alcoholic nectar, attracting slow loris, pen-tailed treeshrews, plantain squirrels and others5. Intentionally or not, warthogs, baboons and giraffes have been recorded getting drunk on marula fruits, and local legends tell that even massive elephants get a bit blatted from time to time6. Fruit flies, far from us on the taxonomic tree, appear to prefer alcohol when given the choice3. This fondness has probably evolved multiple times in different lineages, but perhaps it is also more ancient than previously believed.

Wiens et al 2008 Fig. 1

And there is no doubt that St Kitts’ simians are happy to steal swigs. These are not a local species – St Kitts has no native primates – but rather green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabeus) hailing from West Africa. Their presence on the Caribbean island, as well as nearby Sint Eustatius, St Maarten, Tortola and Barbados, can be blamed on a historical fashion for monkeys as pets. Their identity as green monkeys has been confirmed genetically from their droppings7 but their exact origins are hard to pin down: while a dedicated treatise from the ‘80s did well to get the ball rolling, there still isn’t a definitive history. It’s likely they came from Senegal or Gambia as this is where French ships would port in the mid-to-late 1600s before crossing the Atlantic. But we don’t know if an introduced Cape Verde population features in their family histories and we can’t be sure that similar species weren’t blindly mixed into the gene pool, given that the green monkey has only been considered distinct for the last two decades. This level of detail may seem frivolous but it could prove valuable knowledge, since St Kitts’ monkeys make for a tantalising experiment in evolution, having likely been isolated ever since import stopped in the early 1700s8. Without a known source population to compare to, it’s hard to say how much they’ve changed.

Isabelle Acatauassú Alves Almeida | Flickr

Present

The monkeys also make for an interesting experiment in ecology and sociology, and those are a bit easier to study in real time.

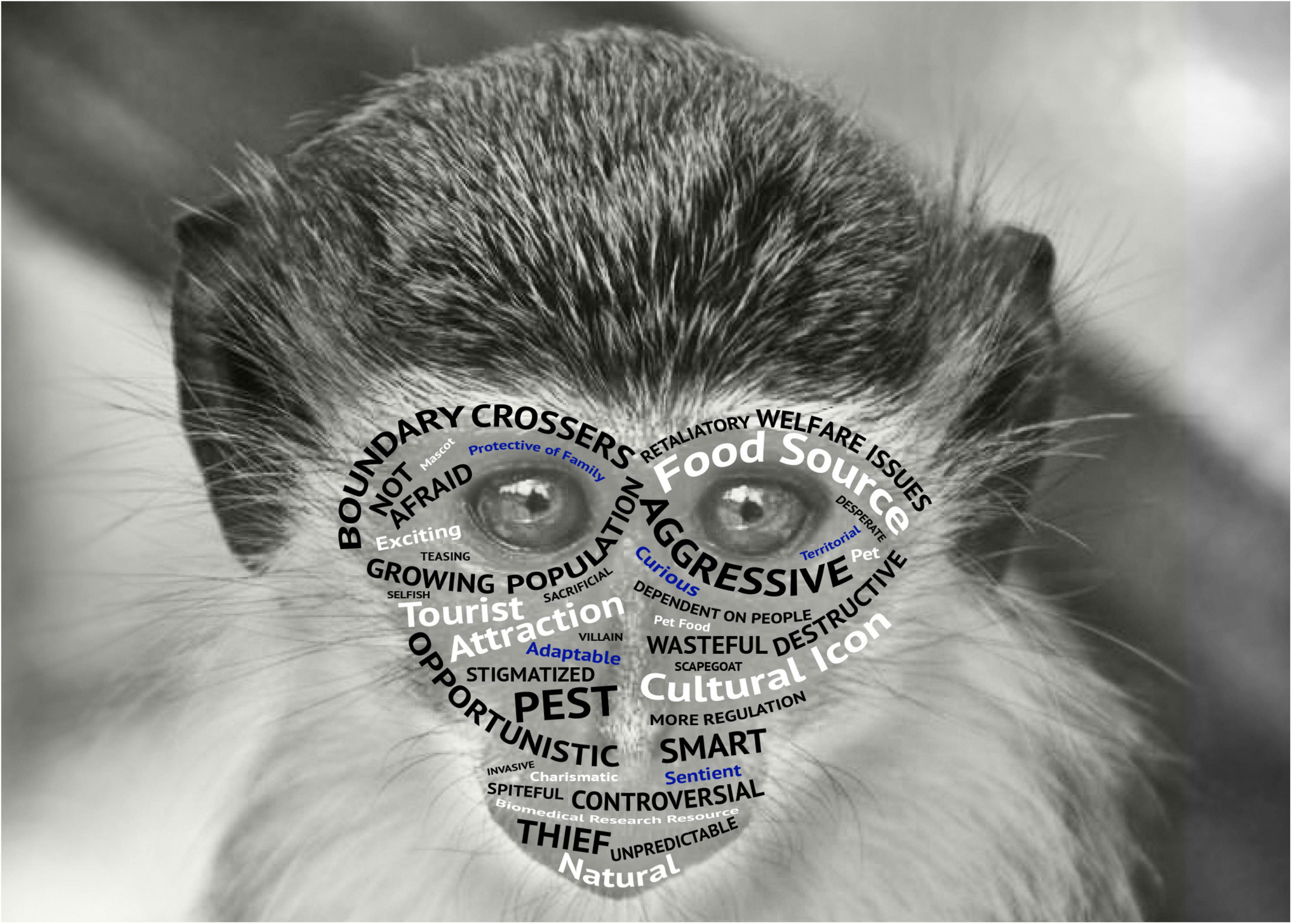

Today, green monkeys on St Kitts number 22000 to 37000 individuals, threatening to equal the human population, on an island of just 176 square kilometres! An animal this large in such high densities on a small island inevitably spells conflict: as early as the year 1700 they were considered pests, “extremely numerous and virtually unavoidable” according to Denham’s treatise8. Sugar farming was St Kitts’ main economy and remained so until recently, armed rangers keeping the monkeys out of the arable lowlands. Confined to the mountainous centre, they were considered only an annoyance by upland smallholders and an alternative food source by everyone else9. However, come the new millennium, an economic switch towards tourism removed motivation for a barrier of bullets and the unabated monkey population is now considered an attraction; they’ve spread rapidly as a result. This is all to the woe of the remaining farmers, with some 50-75% of farms impacted by simian raids10. Though agriculture contributed less than 2% of local GDP between 2012 and 2022 compared to the 60% provided by tourism, it is a sector prioritised by the government for “growth, innovation and development”11, and telling the farmers that their crop losses aren’t too damaging for the nation’s broader economy isn’t of much comfort. Despite their losses, Kittitian farmers are very equitable towards their rascally neighbours: the monkeys are respected for their human-like primate qualities, considered intelligent and understood to need food just as much as people do. Locals take issue not with them taking enough to live on, but with their wasteful and destructive behaviour when they steal more than they need9. Besides agricultural damage, concerns around St Kitts’ green monkeys centre on the threat of injury and disease they pose to people, and vice versa11.

Despite all of this concern, there are plenty of people who laud the presence of the monkeys. As touched on before, they are seen as a great draw for the booming tourism sector, whether encountered roaming free or through paid experiences petting and posing with wild captives (a practice which can raise animal cruelty concerns). They are also a source of animals for one of St Kitts’ more unusual big industries: biomedical and psychological research. Three major facilities operate here, two having sprung up since 2012, pulling monkeys from the wild to fuel scientific and economic endeavours whilst helping to control populations of this introduced species12. Beyond such tangible benefits, St Kitts’ monkeys are considered a cultural icon for the island11, not unlike the barbary macaques of Gibraltar.

Megan F Davis | Gallagher et al 2022 Fig. 1

Considering their local importance, shockingly little ecological research has been done on the green monkeys so far. Anecdotes, preliminary findings and the simple logic that one small island shouldn’t host a lot of introduced, generalist primates so far imply that the monkeys likely put a great amount of pressure on St Kitts’ wildlife. They rip the unopened leaves off “special concern” Acrocomia aculeata palms to reach their tasty young shoots, and chew the succulent bases of Heliconia plants, which are in decline12. Green monkey abundance correlates with another invasive omnivore, the black rat, which benefits from the fruit dropped by their fellow foreign foragers12. Dietary and seed dispersal studies are currently underway, with early work confirming that the monkey population consumes a wide variety of native flora11, but there remain an enormous number of unanswered questions for this controversial creature.

Among major points of interest is the St Kitts monkeys’ curious drinking habit. Once again, little ecological research has been done on the extent to which the unusual nutrient source sustains high numbers of monkeys, whether they are drawn to the area or just make use of what happens to be available, or how behaviours among the stiff-drinking simians affect their environment. Do they show higher population densities near alcohol sources? Are they rowdier, more territorial, or more destructive? Are they perhaps less amenable to wandering the landscape, tied down by their need for good sources of liquor? Most studies on the monkeys’ drinking problem have focused on alcoholism as a medical matter, treating them as a model species for studying dependence in people. A study of 35 monkeys in the wild found that females drank more than males and that (post-pubescent) youths drank more than adults, perhaps due to metabolic differences13. An experiment in 1990 saw only 17% of 196 wild monkeys prefer their sucrose solution spiked, but that both consumption and tolerance increased with time14. Some of these monkeys didn’t know when to stop, even passing out, though drunken behaviour depended on the individual: some became boisterous and cheeky, falling off perches and pulling tails; others were overwhelmed with affection; others still were surly drunks, sat on their own and scowling at their cagemates. Those who drank until they dropped suffered hangovers, avoiding the drink the morning after whilst “huddled quietly in a corner and hypersensitive to abrupt noises”14. When the researchers hid the hootch, many monkeys became irritable, even aggressive, pacing their cages and rattling their alcohol-free water bottles. This is all quite alarming, partly because it seems rather cruel on the monkeys, but also because these symptoms and behaviours are so uncomfortably familiar. Youngsters drinking more than adults, peculiar drunk personalities, horrible hangovers and insufferable withdrawal symptoms. It’s all so human, but maybe this is unsurprising, since we are all so primate.

Future

Nearly 2000 monkeys were removed from St Kitts between 2010 and 2013 through official programs. Over twice this number were culled on nearby Nevis across 2018-2019 through more informal hunting. A surprising amount have also been removed for biomedical research: ~12700 since 1972 by one facility, 1595 since 2015 by another, ~500 (including Nevis) since 2012 by a third12. The green monkey’s future on the island is a large and difficult question, with local negative impacts on one hand, economic boon and cultural emblem status on the other, balanced in a stark vacuum of missing information. The ‘monkey problem’ is a hot topic for Kittitians, with the phrase in itself belying a common awareness that filling a small Caribbean island with medium-sized primates is probably not good in a lot of ways, but getting rid of them isn’t so easy. There appears to be a growing danger that the St Kitts economy, and perhaps part of its identity, are becoming dependent on these potentially damaging primates just as those caged monkeys grew dependent on their alcoholic sucrose solution.

So long as the green monkeys remain on the island, they continue to evolve in isolation, adapting to an environment quite different from their original West African forest home. The work of Turner et al (2018) suggests three short centuries may have already seen them develop unique traits: they are more sexually dimorphic than native African populations (with males the larger). Comparing across St Kitts, Ethiopia, Kenya and South Africa, green monkeys also weakly follow two evolutionary trends: Bergmann’s rule of size increase and Allen’s rule of shorter limbs as distance increases from the equator. Studies in the 1950s and ‘60s found that St Kitts monkeys have larger, less-variable teeth than average for the species (though still within the normal range)15 and speculated that, given another 5000 years, their gnashers could fully double in size16 (along with other bits of them, presumably, or they might end up looking rather toothy). Turner’s team posited that if the monkeys underwent boom-and-bust cycles on the island, growing in population, depleting resources and collapsing only to build back up when the island recovers, evolutionary forces could be accelerated17. However, these trends may be a mere coincidence caused by random biases in the small pool of monkeys taken to St Kitts in the first place, representing traits which just happened to be present in the founding few plucked from a wider population. While a founders’ effect might sound underwhelming compared to island monkey evolution, it still shows that St Kitts’ green monkeys are intriguingly unique, with their own gene pool and population make-up distinct from any other. That uniqueness may be slight now, but it will keep growing as long as isolation is maintained. If they were left in place for millennia to come, maybe St Kitts would one day be home to its own monkeys found nowhere else on Earth.

Didier Desouens | Wikipedia

References

1Dudley R & Maro A. 2021. Human evolution and dietary ethanol, Nutrients, 13(7), 2419 | Link

2Carrigan MA, Uryasev O, Frye CB & Benner SA. 2014. Hominids adapted to metabolize ethanol long before human-directed fermentation, PNAS, 112(2), pp. 458-463 | Link

3Peris JE, Rodríguez A, Peña L & María Fedriani J. 2017. Fungal infestation boosts fruit aroma and fruit removal by mammals and birds, Scientific Reports, 7, 5646 | Link

4Hockings KJ, Bryson-Morrison N, Carvalho S, Fujisawa M, Humle T, McGrew WC, Nakamura M, Ohashi G, Yamanashi Y, Yamakoshi G & Matsuzawa T. 2015. Tools to tipple: ethanol ingestion by wild chimpanzees using leaf-sponges, Royal Society Open Science, 2(6), 150150 | Link

5Wiens F, Zitzmann A, Lachance M-A, Yegles M, Pragst F, Wurst FM, von Holst D, Leng Guan S & Spanagel R. 2008. Chronic intake of fermented floral nectar by wild treeshrews, PNAS, 105(30), pp. 10426-10431 | Link

6Makopo TP, Modikwe G, Vrhovsek U, Lotti C, Sampaio JP & Zhou N. 2023. The marula and elephant intoxication myth: assessing the biodiversity of fermenting yeasts associated with marula fruits (Sclerocarya birrea), FEMS Microbes, 4, xtad018 | Link

7van der Kuyl AC & Dekker JT. 1996. St Kitts green monkeys originate from West Africa: genetic evidence from feces, American Journal of Primatology, 40(4), pp. 361-364 | Link

8Denham WW. 1987. West Indian green monkeys: problems in historical biogeography, Contributions to Primatology, 24. Basel, Switzerland: S Karger. | Link

9Dore KM. 2013. An anthropological investigation of the dynamic human-vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) interface in St Kitts, West Indies, The University of Wisconsin – Milwaukee ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 3615733 | Link

10Dore KM, Eller AR & Eller JL. 2018. Identity construction and symbolic association in farmer-vervet monkey (Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus) interconnections in St. Kitts, Folia Primatologica, 89(1), pp. 63-80 | Link

11Gallagher CA, Hervé-Claude LP, Cruz-Martinez L & Stephen C. 2022. Understanding community perceptions of the St Kitts’ “Monkey Problem” by adapting harm reduction concepts and methods, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 10, 2022.904797 | Link

12Dore KM. 2019. Critical situation analysis (CSA) of invasive alien species (IAS) status and management, Federation of St Kitts and Nevis | Link

13Juarez J, Guzman-Flores C, Ervin FR & Palmour RM. 1993. Voluntary alcohol consumption in vervet monkeys: individual, sex, and age differences, Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behaviour, 46(4), pp. 985-988 | Link

14Ervin FR, Palmour RM, Young SN, Guzman-Flores C & Juarez J. 1990. Voluntary consumption of beverage alcohol by vervet monkeys: population screening, descriptive behaviour and biochemical measures, Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behaviour, 36(2), pp. 367-373 | Link

15Poirier FE. 1972. The St. Kitts green monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus): Ecology, population dynamics, and selected behavioural traits, Folia Primatologica, 17(1-2), pp. 20-55 | Link

16Ashton EH. 1960. The influence of geographic isolation on the skull of the green monkey (Cercopithecus aethiops sabaeus) V. The degree and pattern of differentiation in the cranial dimensions of the St Kitts green monkey, Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 151(945), pp. 563-583 | Link

17Turner TR, Schmitt CA, Danzy Cramer J, Lorenz J, Grobler JP, Jolly CJ & Freimer NB. 2018. Morphological variation in the genus Chlorocebus: ecogeographic and anthropogenically mediated variation in body mass, postcranial morphology and growth, American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 166(3), 682-708 | Link

18Gonedelé Bi S, Galat G, Galat-Luong A, Koné I, Osei D, Wallis J, Wiafe E & Zinner D. 2020. Chlorocebus sabaeus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e.T136265A17958099. |Link

19Nobimé G & Imong I. 2020. Cercopithecus mona. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2020: e/T4222A17946672 |Link

20Martonos CO, Gudea AI, Ratiu IA, Stan FG, Bolfă P, Little WB & Dezdrobitu CC. 2023. Anatomical, histological, and morphometrical investigations of the auditory ossicles in Chlorocebus aethiops sabaeus from Saint Kitts Island, Biology, 12(4), 631 | Link

21Dore KM, Gallagher CA & Mill AC. 2023. Telemetry-based assessment of home range to estimate the abundance of invasive green monkeys on St Kitts, Caribbean Journal of Science, 53(1), pp. 1-17 | Link

22BBC Studios/BBC Worldwide. 2009. Alcoholic vervet monkeys! – Weird Nature – BBC animals, hosted by YouTube | Link

23Dudley R. 2000. Evolutionary origins of human alcoholism in primate frugivory, The Quarterly Review of Biology, 75(1), pp. 3-15 | Link