We’re often told to think big, dream big, see the big picture, but small should not be underestimated. Small things can have a big impact, and it turns out this is especially true for mongooses. Once given the scientific name Herpestes auropunctatus, the small Indian mongoose has been moved to the genus Urva. This is a suitable new moniker given the diminutive animal is busily ‘Urva-whelming’ island ecosystems across the tropics.

The small Indian mongoose is an adaptable animal native to southern Asia, from Iran through India across to Myanmar. No more than a couple of feet in length, it eats almost anything it can get hold of, from small mammals and birds to insects to fruit and other inviting bits of plant. They’re not picky about location either, preferring dry grassland but also recorded doing well in forest, rainforest and the concrete jungle1 (where human rubbish is a widely-available delicacy2). This incredible flexibility, with the help of people, has made the small Indian mongoose one of the most infamous invasive species in the world. Perhaps nowhere is this infamy greater than the remote volcanic archipelago of Hawaii.

J.N. Stuart | Flickr

Correlation and Causation

In the late 1800s, the sugarcane industry of the Caribbean was going strong. The latest experiment in increasing profits sought to remove a crop pest which was damaging export: rats. A portable little carnivore had been identified by British corporate interests in India and the small Indian mongoose was released into Jamaica’s crop fields in the early 1870s2. To the delights of plantation managers, crop yields increased! A suitcase nuke capable of taking out vermin and increasing profits whilst sustaining themselves with minimal effort seemed like a dream solution, inspiring releases across the West Indies and beyond.

But the releases were misguided. First of all, small Indian mongooses hunt during the day while rats are nocturnal. And with an island full of naïve ground-nesting birds, lizards and turtles, native species proved far easier prey to the unfussy mustelids.1, 2, 3. The rises in sugarcane yield were most likely the result of unrelated management changes at the time.

The Hawaii Invasive Species Council4 is eager to point out that this was not a failed biocontrol programme. Such a crude, uninformed, unscientific attempt by private profiteers doesn’t sit in the same category as the cautious, highly-targeted and highly-monitored efforts of the modern day. It was as close to biocontrol as strapping a hefty firework to your back is close to space travel.

Invading Hawaii

The late 1800s saw the mongoose inflicted on Hawaii Island (Big Island), Maui, Moloka’i and O’ahu, with Kauai spared only through happenstance. Local legend has it that when the original shipment of animals was being unloaded, one of the mongooses bit the dockworker carrying them. He responded by chukcing the crate into the sea, killing its unfortunate contents.3

Today, there are new sightings of small Indian mongooses on Kauai every few years. No sustained population has yet been discovered but these reports demonstrate a worrying potential for establishment. After all, the species has been accidentally introduced elsewhere by hitching a ride on cargo ships, so may not need to rely on intentional release to spread around the nautical state.

This ‘gourmand-goose’ munches its way through turtle eggs and kills native bird species. It has contributed to the declines of rare birds like the Hawaiian crow (now extinct in the wild), Hawaiian petrel and the state bird, the Hawaiian goose; similar impacts, or even extinctions, have been faced elsewhere by the bar-winged rail, Caribbean petrel, Hispaniolan racer and Amami rabbit. They are also a vector of rabies and destroyer of poultry. Summing these together, Pimental et al (2000)5 calculated a combined cost to Hawaii and Puerto Rico of $50 million every year – an extra quarter-century of population growth means this figure has presumably risen.

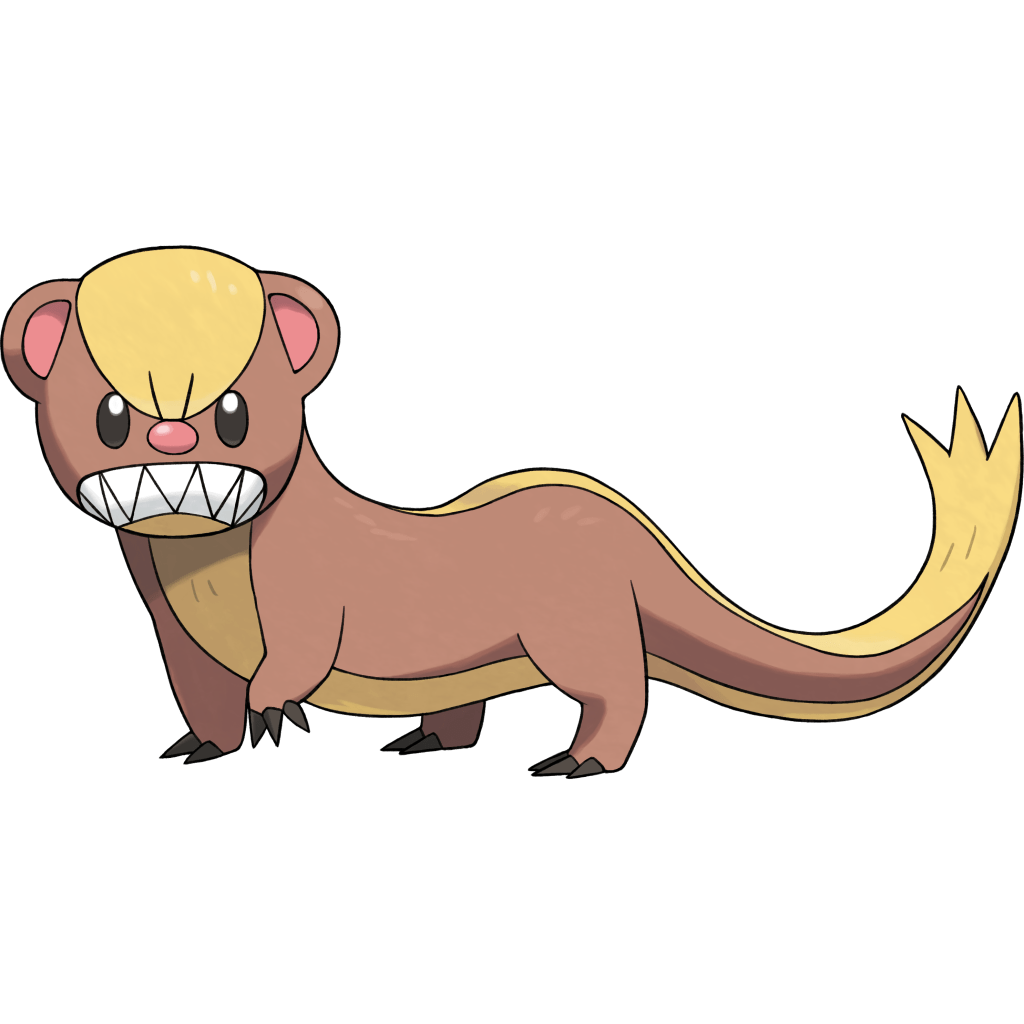

The small Indian mongoose’s veracity has earned it such a reputation that is has even been immortalised in popular culture as a Pokémon!

Ken Sugamori | Pokémon | taken from Bulbagarden

Making it Complicated

When it comes to ecology, nothing happens in isolation. The invasive mongoose is no exception and, despite its infamy, comes with some silver linings. For one, it will happily eat fellow invasive species such as anoles and iguanas1. For another, if what is true of Mauritius applies also to Hawaii, removal of the mongoose could allow rats and cats to run wild and wreak even greater havoc on native species1.

Besides, there is an argument to be made that the mean mongoose reputation is not deserved. That argument is made by expert Buzz Hoagland in an article by Matthew Miller and points out that there are many other factors threatening native island fauna, such as disease spread through bird populations by introduced mosquito species. Buzz warns that there’s a danger in using the mongoose as a scapegoat, treating its removal as a cure-all while ignoring the myriad of other issues facing tropical island habitats.

J. N. Stuart | Flickr

Nevertheless, the mongoose itself is a problem. Given the chance, its adaptability has allowed it to thrive from Fiji to Jamaica, Okinawa to Croatia, and, of course, across the islands of Hawaii. There is no doubting the damage this diminutive devil does, but it’s hard not to be a little impressed with this pernicious little predator.

References

1Roy S. 2016. Herpestes auropunctatus (small Indian mongoose), CABI Compendium. | Link

2Miller ML. 2015, updated 2018. Island mongoose: conservation villain or scapegoat? Or both?, Cool Green Science: Stories of the Nature Conservancy. | Link

3Mongooses in Hawaii: why latest finding on Kauai is so disturbing, Beat of Hawaii. 2021. | Link

4Mongoose, Hawaii Invasive Species Council. 2024. | Link

5Pimental D, Lach L, Zuniga R & Morrison D. 2000. Environmental and economic costs of nonindigenous species in the United States, BioScience, 50(1), pp. 53-65 | Link