Updated 18/06/2023

It is a tendency of we British to enjoy complaining about trivialities. Our culture nurtures the paradoxic ability to celebrate concepts by lightly slandering them: to take the time to make an item a source of habitual grumble, to put it on a pedestal of deprecation, is to show that it is in our hearts and minds. Thus it is that British birders, with a smirk and a roll of the eyes, will often remark how evolution has blessed us with a myriad of the muted, a plethora of plain, a bounty of banality. An overabundance of ‘little brown jobs’. Yet, every good British birder knows it, we have a number of wonderfully colourful species here. The citrus tones of the green woodpecker, the extraordinary bill of a breeding puffin, the lurid iridescence of a summer starling; and the absolute height of our avian colour, the kingfisher. But there are some fluttery friends lying just beyond our borders which might put even these vibrant avians to shame. Among them is the European bee-eater, and every so often they push their continental status by emigrating to Britain for the summer. With global warming ever changing this green and pleasant land, there are those who forecast bee-eater visits as a regular feature of the future.

Past

Have you ever gotten up early in the morning, looked at yourself in the mirror and pondered ‘am I a turanian-mediterranean faunal element’? I haven’t. Maybe some of you have. Maybe some bee-eaters have as well, this being the wonderfully eloquent and indulgently sciencey descriptor applied to them by Stiels et al (2021). Sounds better than “lives around the Med and west-central Asia”, doesn’t it? Genetic analysis suggests the European bee-eater emerged as a distinct species some 3 million years ago, since when it has spread its breeding range across Europe, through central Asia, right up to western China and Mongolia. In a further blow to the logic of its English name, many of these birds spend the northern winter in sub-Saharan Africa and, to really rub it in, some even stay south to breed in Namibia and South Africa. Not so European after all, eh?

Image: Bernard DUPONT | Flickr

This southern African population, which BirdLife International considers non-migratory but which may spend part of the year in Malawi, appears to be a fairly recent revolution, as the southern-breeders are not yet distinct from their north-going counterparts (according to de Melo Moura et al, 2019). At least, it must be recent if we assume birds aren’t keeping the genes flowing by switching between northern and southern breeding grounds… migratory plasticity is a complex topic for this species. Genetic differences between west Europe, east Europe and west Asia have formed along migratory pathways over the last 600 000 years or so, suggesting there is constancy in how the generations make their way over the globe. On the other hand, a 2016 study may have identified a change in migration route and establishment of a new Iberian colony of bee-eaters distinct from the usual residents. Knowing this, how readily could European bee-eaters shift their breeding range north, into Great Britain?

Major climate-driven range shifts must have occurred in this species in the past, seeing as this is a Palaearctic bird and much of that realm used to be under ice. Actually, their northern limit has undulated over the species’ three-million-year existence, ice sheets pushing them into refugia only for them to advance north again in the interglacial periods. These biogeographical wobbles have left a genetic imprint, as post-glacial expansion events saw admixture between populations bouncing back from their isolated ice-free sanctuaries. An abundance of rare polymorphisms (that is, lots of uncommon, differing and unique sets of genomes) in modern birds suggests recent positive selection for genetic diversity and interbreeding to make up for the frozen barriers of the last Ice Age. This all tells us that European bee-eaters have a history of climbing up the map when temperatures rise, but bear in mind this usually happens at geological timescales and human-driven climate change is happening with unprecedented speed. Will the rainbow-coloured bug-munchers keep up?

Present

“When environmental conditions change, species usually face three options: adaptation, range shifts, or extinction… it is generally believed that range shifts are the norm in mobile species such as birds.”

This quote, from Stiels et al, covers things quite nicely: adapt, move or die. As bee-eaters are endowed with the gift of flight and already traverse a good part of the planet’s circumference each year on migration, they should be very capable of keeping ahead of poleward temperature climbs. Range shift responses to global warming follow something called niche tracking: the tendency or ability of a species to follow its climatic niche over time. The climate changes, a given temperature band moves to more extreme latitudes, and the species evolved for those temperatures must move too. That’s not to say all of a current range will be rendered inhospitable by climate shifts: it can mean new territories open up at one extreme while they must be abandoned at the other. But it isn’t yet clear if niche tracking is the usual response even in motile animals, as these species still face limits to their movement or adaptability and tend to lag behind their advancing climates.

The bee-eater, however, seems more capable than some in keeping up with modern climate change. Across western and central continental Europe, breeding has been recorded at increasing latitudes: Switzerland, Poland, Slovakia, France and especially Germany have seen remarkable range expansion. Some of these countries are but a hop across the North Sea or English Channel, a journey which bee-eaters have made a number of times, as I can attest.

Image: IRahulSharma | Flickr

In the Spring of last year, I offered myself as an RSPB volunteer to spend a few nights watching over bee-eater nests in a small quarry in north Norfolk, protecting the young from possible predators and poachers. This was immensely exciting to me, as these birds are not normally seen in the country, let alone breeding. I felt as though I was witnessing the arrival of a new native species to Great Britain! Of course, the volunteering itself was fairly mundane: I would load myself up with snacks (the more sugary or caffeinated the better), then challenge myself to stay awake all the way to sunrise by chitchatting, staring at the stars, patrolling the site and occasionally shining a torch across the face of the quarry to shoo foxy or human pilferers (I saw none). We burrow bodyguards were lucky enough to be given a pair of infrared goggles as added entertainment (and essential lookout tool), so I also got to pass a little time looking for the glowing ovals of owls and watching their vole prey skitter about the quarry walls. Come morning, having been awake for 26 hours or more, I was rewarded with incredible views of the colourful birds lined up on telegraph wires or swooping off into the surrounding fields. I was only able to offer up a few of those long nights and missed the rare British bee-eaters’ fledging, but a total of five young left those Norfolk nests for the big wide world.

Although unusual, this was not an isolated case. I couldn’t find an official list of breeding attempts in the UK but Wikipedia offers 8 including last year’s: a pair in Scotland in 1920 who were captured and died after laying a single egg; two pairs in 1955 raising seven young despite one nest being destroyed by machinery; two birds which fledged from a nest in 2002; failed attempts in 2005 and ‘06; two pairs in 2014 and 2015 with unknown success; another failure in 2017; and Norfolk’s five fledglings in 2022. You may notice the majority of these took place in the New Millenium, albeit with only a few chicks leaving the burrow. People are perhaps far better at finding and reporting these breeding attempts than they once were, and less willing to quietly snatch up the birds for the black market – the RSPB has taken great effort to watch over every nest since 2005. Even so, seven attempts in 20 years compared to two attempts across the century before seems like a remarkable rise.

UPDATE: Amazingly, just a few days after I first published this post, bee-eaters have again been reported from the Norfolk quarry. Likely some of the same birds as last year, if annual visits continue this could represent the start of a persistent British population!

Bee-eaters are not alone in their British excursions. Between 2008 and 2018, some 55 different species were recorded to have moved to new territories in the UK, though almost all of them were existing natives which nudged up their northern boundaries. Only one species was a first-time breeder in the country between those years: a black bee-fly with the unnerving name Anthrax anthrax. A full list of niche trackers doesn’t appear available but highlights are listed in a press release, including the wasp spider, Jersey tiger moth, red mullet and greater horseshoe bat. The authors of the study found 24% of the 55 species to have negative ecological or social impacts; the European bee-eater was part of the 20% bringing positive impacts, mainly tourism, alongside the little egret and purple heron. I won’t dare to deconstruct the impacts of these aberrant animals right now, but it’s obvious there is change afoot (and, I suppose, awing).

Image: Bas Kers (NL) | Flickr

Future

While I was watching over the Norfolk bee-eater nests, among the meandering conversations I had with the RSPB official nest-guarding with me, I asked whether breeding events were ever likely to become the norm. He told me he didn’t believe bee-eaters would ever become stable residents of the UK due to a lack of insect prey under our country’s intensive land use and to our changeable weather. After all, that year’s batch of birds had found themselves in a remarkably hot British summer, at a quiet agrarian spot with sandy quarry walls and their own buffet beehives. It was hardly representative of the typical English country experience, and our danker years may be too inhospitable for this species.

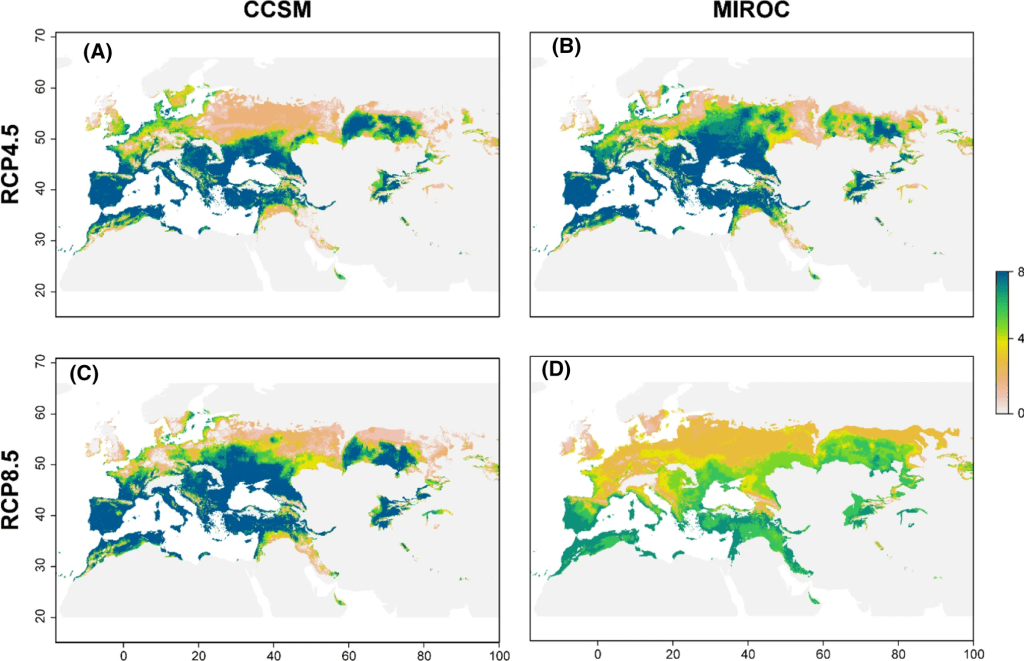

There has been a formal scientific study on the future climate’s suitability specifically for European bee-eaters, which was a lucky break for me writing this. Yes, I’m again referencing Stiels et al, all of whom I owe a cool beverage at this point. Using a combination of climate prediction models, they suggest that Cornwall, Devon and East Anglia, perhaps north as far as Liverpool, could become suitable by 2050 under moderate global response RCP 4.5. This same model combination showed that bee-eaters could range as far north as southern Sweden, the Baltics and southern Russia under these conditions, without losses in their southern European or Maghreb range. Under RCP 8.5, less of England was suitable in 2050 with one model from the set excluding it completely. These models are a tantalising prediction but they aren’t perfect, failing to identify existing parts of bee-eater range in eastern Europe and over-predicting presence around the North and Baltic Seas. Belarus proved especially deviant and its removal from models “improved that relationship [between model and reality] tremendously”. The scientists themselves warn that “we do not recommend to infer generalizations from the results of our single species study in a limited geographical area” but provide the defence that some inaccuracies may be down to failures in actual population monitoring. It’s amusing to think that their climate modelling could be more accurate than real, actual records of real, actual birds! But it is only climate modelling, and there is plenty else limiting bee-eater populations (as bemoaned by my burrow-watching buddy). Wintering grounds and migration routes are also not modelled but climate change is undoubtedly having an effect in those areas.

So what can we say about a future British range for the European bee-eater? Little with certainty, but it looks likely that bee-eaters will spread north in Europe and reach into the fringes of the UK if (and only if) there is enough insect life for them to feed on and enough habitat for then to nest in. I’m sure its name will stir up the more sensitive apiarists in the country but given that ecosystems are pretty similar each side of the Channel, it seems unlikely that this bird will be anything other than a treat of colour should it cross into Britain for good. And it can join the other vivid avifauna which we British will quietly celebrate between snarks and remarks about boring brown birds.

References

Anderson S. 2022. Bee-eater brood up to five as group gets ready to fly!, North Norfolk News | Link

Arbeiter S, Schulze M, Tamm P & Hahn S. 2016. Strong cascading effect of weather conditions on prey availability and annual breeding performance in European bee-eaters Merops apiaster, Journal of Ornithology, 157, pp. 155-163 | Link

Ashe I. 2017. Rare bee-eater nests which attracted thousands of twitchers to Nottinghamshire have failed, Nottingham Post | Link

de Melo Moura CC, Bastian H-V, Bastian A, Wang E, Wang X & Wink M. 2019. Pliocine origin, ice ages and postglacial population expansion have influenced a panmictic phylogeography of the European bee-eater Merops apiaster, Diversity, 11(1), 12 | Link

Pettorelli N, Smith J, Pecl GT, Hill JK & Norris K. 2019. Anticipating arrival: tackling the national challenges associated with the redistribution of biodiversity driven by climate change, Journal of Applied Ecology, 56(10), pp. 2298-2304 | Link

Ramos R, Song G, Navarro J, Zhang R, Symes CT, Forero MG & Lei F. 2016. Population genetic structure and long-distance dispersal of a recently expanding migratory bird, Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 99, pp. 194-203 | Link

Scandrett K. 2019. Species on the move, British Ecological Society. | Link

Slack R. 2005. Breeding Bee-eaters in Herefordshire, BirdGuides.com | Link

Stiels D, Bastian H-V, Bastian A, Schidelko K & Engler JO. 2021. An iconic messenger of climate change? Predicting the range dynamics of the European bee-eater (Merops apiaster), Journal of Ornithology, 162, pp. 631-644 | Link

UPDATE: Gayle D. 2023. Exotic bee-eater returns to UK for second summer in a row, The Guardian | Link