In 1901, John Tunney collected an animal he didn’t recognise. He sent it off to his benefactor in the UK, where the specimen joined thousands of other items as part of the famous Rothschild collection, and disappeared from all knowledge. Until two centuries later, when researchers at the British Museum of Natural History rediscovered Tunney’s lost animal, launching them into a detective mystery a century in the making.

Tunney’s animal is a western long-beaked echidna, and was identified once it arrived in England. Except that the circumstances of its collection, re-examinations, miscorrections and doubts mixed up the details and 100 years of obscurity have left knots to unravel. The problem at the core: this specimen was found somewhere this species doesn’t live, or at least where it has never been reported by anyone since. So did Tunney’s animal really come from Australia, and if so, was it the only one?

Credit: G Creutz | Wikipedia

Past

Monotremes are a famously unique group, with Gondwanan origins. Experimental data suggests they split off from all other mammals around the Triassic-Jurassic border some 200 million years ago5, evolving around the ankles of Diplodocus, Stegosaurus and Allosaurus. They once lived across the southern continents of what are now South America, Antarctica and Australia4,5, back when they formed the single continent of Gondwana. Monotrematum from Argentina proves this as the only monotreme fossil ever found outside of Australia, living in the quiet world left after the extinction of the dinosaurs 61 million years ago4,5.

The monotreme fossil record contains much more gap than it does fossil, and monotreme evolution has been a difficult debate for decades. This post nearly became one huge tangential exploration of these weird creatures’ origins, but I’m going to show restraint and offer only a quick overview for what people seem to think now. The earliest known monotremes, roughly 200 million years old, were Teinolophus and Steropodon which definitely bore resemblance to today’s platypus but looked a lot more shrewish or mole-y. Another 50 million years later, Monotrematum was swimming around busily being an early true platypus and looking really quite a lot like the one living in Australia today. Skip ahead another 25 million years or so and echidnas broke off from the platypus lineage to forge their own way. Steaming ahead to the present day, we see two living families: the modern platypus in Ornithorhynchidae and the echidnas in Tachyglossidae.

Credit: Ghedoghedo | Wikipedia

Mammals are quite strange: hairy, high-gaited, messy-toothed, smooth-skinned freaks who leak milk to their young and often have silly ear flaps. But if mammals are weird, then monotremes are really weird, sweating milk but laying eggs. And if monotremes are really weird, the web-footed, beaver-tailed, duck-billed chimera that is the platypus is really weird. But the undisputable, indubitable, absolute King of the Weird is the echidna. Why? Because platypuses evolved over 60 million years ago, and sometime since one little group decided they were sick of the waterways and climbed back on land to dig through dirt and eat ants. That’s right: modern evidence suggests echidnas evolved from, and therefore are, fat, spiny, spade-footed platypuses4,5. I’d love to keep writing about how freaking weird and amazing these things are, but I have to move on or this article will never end.

Eight echidna species are known from the fossil record up to the present day, falling into three (or possibly four) genera. From these, four species are known to have lived in Australia: Megalibgwilia owenii, “Zaglossus” hackettii (the giant echidna, which may belong to another genus), the western long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bruijnii and the short-beaked echidna Tachyglossus aculeatus. Only the latter of these is known from Australia today, but the rest persisted there into the late Pleistocene and met Australia’s first human occupants1. In a tale familiar to much of Australia’s megafuana, these adventurous first people were likely over-exuberant in their hunting and doubled down on the climate pressures already threatening the continent’s ecosystems at that time.As far as most of the world is concerned, all but the short-beaked echidna were wiped out in Australia, though a few other echidnas persist in New Guinea. Most people have been fairly solidly sure that just the one echidna skulks around the outback nowadays.

Most people. For a while.

Present

In 2009, a skin was uncovered in the British Museum of Natural History1. It bore the tags of John T Tunney who, at the time, was leading the first cataloguing of mammals in the western Kimberley region in Western Australia. Tunney had given no species, but eminent mammologist Oldfield Thomas had filled in this blank, naming it as a western long-beaked echidna. And yet modern understanding of echidnas suggests this animal was wrong. Not the identification, Oldfield knew what he was doing and got it perfectly right, but this species of echidna lives in western New Guinea, not Australia. Despite being held by some of the time’s most prominent naturalists, no paper was ever published on the specimen directly. The anomaly led a small team of researchers1 down a winding rabbit hole, chasing paperwork, cross-checking, and tracking this specimen’s weird history. Their conclusion was that Australia’s official echidna count may be one short.

Credit: Helgen et al (2012)

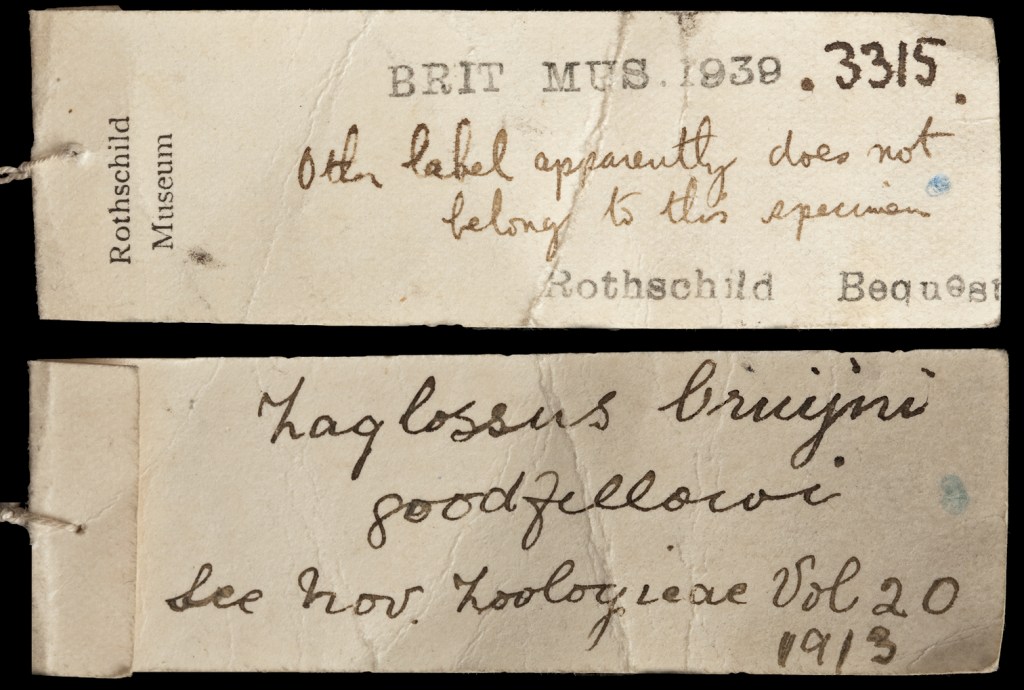

Tunney had caught the echidna on 20th November 1901. He prepared a taxidermy specimen consisting of the skin, most of the skull and the right forearm, giving it the fieldmark 347 and sending it off to the UK. We know he did this because of the date given on his specimen’s tags and because of import paperwork1. But Tunney left the ‘Species’ field blank on his tag, presumably because he wasn’t sure quite what he’d found. On receipt in England, the specimen was noted by Oldfield Thomas who removed and observed the skull and forearm for identification. He concluded it to be an immature Zaglossus echidna, not part of Tachyglossus which contains the short-beaked echidna widely known from Australia, and noted similarity to the western long-beaked Zaglossus bruijnii. From there, the specimen passed to the Rothschild collection1. It went unpublished in the literature, perhaps because Thomas was waiting for Rothschild to make a publication and was hoping for an adult specimen to help in his own study1. The only papers relating to the skin describe a flea and a mite, each found in the dead animal’s fur, and call the specimen a Tachyglossus (short-beaked echidna), likely an assumption based on its location1. Thus, Tunney’s animal passed into obscurity almost immediately.

The specimen went seemingly untouched until 1913 when Fred Young, one of Rothschild’s resident taxidermists at Tring, re-examined the echidna and gave it a new label. This simply stated the existing label was wrong, mismatched. No specific argument was given but, with a touch of snark and irony, Young left a citation for one of Rothschild’s own publications: a summary of the echidnas held in the collection, with a key to their identification. Tunney’s Specimen 347 was not included in this record and the key gave Zaglossus bruijnii’s home range as the island of Salawati, at the time the only place it was known to inhabit. Presented with a specimen which shouldn’t be in the collection and which apparently came from the wrong place, Young wrote it off as a label mismatch. The skin was stuck in a drawer and forgotten about for a hundred years, only seeing some activity when it was unceremoniously renamed BMNH 1939.3314 and moved to the British Museum of Natural History with much of the rest of the Rothschild collection, where it continued its torpor.

Caption: Helgin et al (2012)

But Young’s simple explanation was not the end of the story: when Helgen et al1 found the specimen and tracked down its origins, they gathered a small mountain of evidence that the labels were never switched. The tags clearly show the handwriting of Tunney and Thomas, so it isn’t a forgery. They clearly refer to an echidna, and this is backed up by export/import records. This means the tags must have come from an echidna, of indeterminate specie, so for a switch to have occurred the tags would have had to fall from one echidna and be attached to a second, unlabelled specimen, which seems unlikely. The Western Australia Museum of Perth, the city from which the specimen was sent, has never held a long-beaked echidna and Tunney never made collections in New Guinea, the only confirmed home for this particular species, so there was no other available skin from which the labels might have fallen. Oldfield Thomas noted that his specimen was a Zaglossus species, so if the tag was moved after he had done his work it could only have gone from one Zaglossus to another. It’s also of key interest that Tunney, who was familiar with the short-beaked echidnas we expect to find in Australia, did not identify his Specimen 347 and called it ‘rare’, where his short-beaked echidnas were labelled as a ‘numerous’ species. Most convincingly, the lengths given on Tunney’s label match the lengths of BMNH 1939.3314, to which they are now attached. This seems to leave little doubt that the animal Tunney found, prepared and labelled in Kimberley is the same animal recovered in the British Museum of Natural History so many decades later. The evidence suggests that Tunney stumbled on an Australian population of long-beaked echidnas unknown to science even now, a hundred years later.

A final confirmation of a relict population would be a genetic comparison between specimen 347 and the modern western long-beaked echidnas to prove, once and for all, that Tunney’s animal didn’t come from any group known today. This has complications, however, as the shrunken New Guinea population won’t hold all of the same genetic variety it did in Tunney’s time, and specimens of this animal are few in number. Catching wild echidnas to take blood samples would be extremely tricky as they are reclusive and little-studied, making them difficult to sample in decent numbers. This means any genomic data from Tunney’s echidna would have only a fraction of the original New Guinea population to serve as a comparison. After all, there is no guarantee Tunney’s echidna wasn’t shipped across from New Guinea and released or escaped before being killed and stuffed, though I’m not aware of a precedent for this and the Kimberley region has been only sparsely populated.

Even without a genetic study, there are some major implications here. We have just a single specimen, which is frankly rubbish as evidence usually goes, but everything points to it being the real deal. It really seems that, until at least the 20th Century, Australia had a second species of echidna living in its rural Kimberley region. And it might still be out there.

Helgen et al1 compare the rugged terrain with patches of rainforest to the native habitat of western long-beaked echidnas in New Guinea, and suggest the habitat would have been even more similar until recent climate changes forced the Kimberley rainforest back. They hypothesise that the western long-beaked echidna once saw a healthy, contiguous range from Kimberly up to New Guinea across the now-submarine northern tract of the Sahul continent, a single landmass when sea levels were lower in recent glacial maxima.

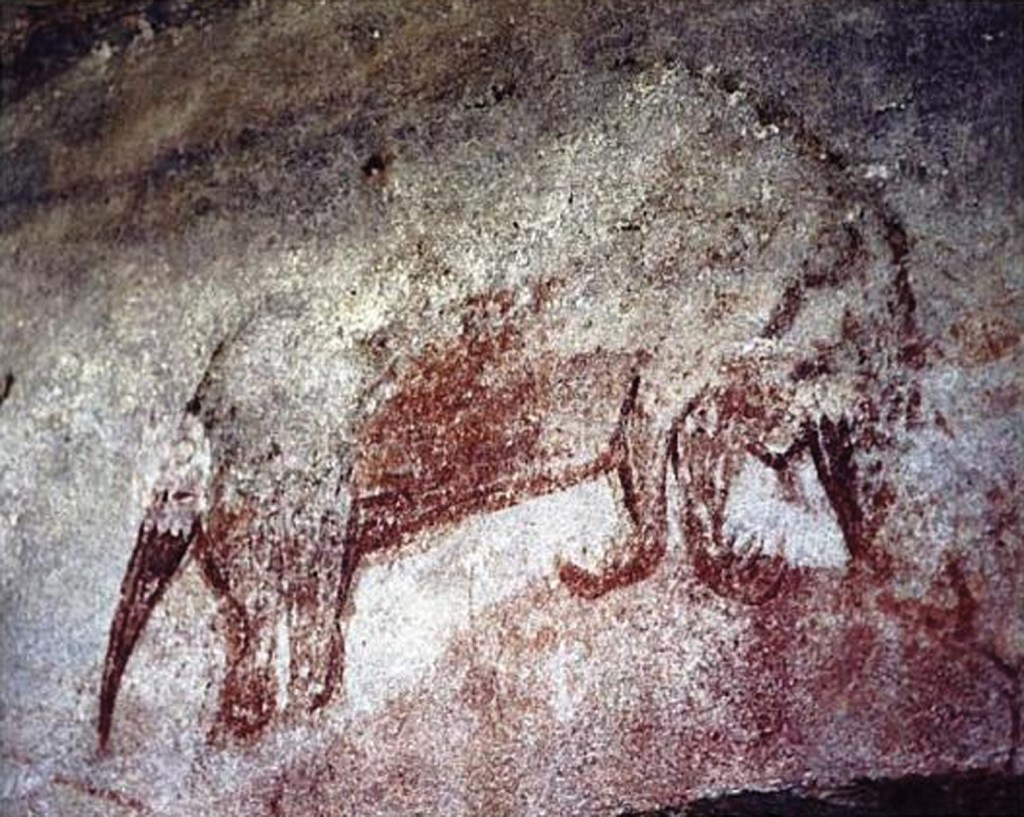

Helgen et al1 point out that a Zaglossus form appears to be painted into ancient rock paintings in Arnhem Land6 and recant an anecdote collected from an aboriginal woman in Kimberley who mentions her grandmother hunted “the other one” (i.e. not the short-beaked echidna), and that same grandmother subsequently recognised Zaglossus from a paper illustrating extinct Australian megafauna1. Of course, this is very minimal evidence, but it’s a promising suggestion that a second echidna species might still exist in Australia.

Credit: Murray & Chaloupka (1984) via Helgin et al (2012), photographed by G Chaloupka

Future

If the western long-beaked echidna still lives in the wilds of north-west Australia, it probably exists in fragmented populations because of the modern state of habitat there1. However, little is known about this echidna’s ecology and it’s range in New Guinea is restricted, so it’s possible it can survive a wider array of habitats than we see today. In it’s known range, this echidna species is critically endangered by agricultural pressures and hunting, including for subsistence7. As things stand, the IUCN lists the western long-beaked echidna as ‘possibly extinct’ in Australia, citing Helgen et al’s recovered specimen but not committing to list it as a formerly (or currently) native species7. The global western long-beaked echidna population hangs in the balance, alongside the other two Zaglossus species which may not see much of the future.

The historical presence of Zaglossus bruijnii in Australia would make it a possible candidate for reintroduction there, not just to restore a former ecosystem function to the area or to increase biodiversity but as a crucial insurance population for the echidna. One hundred years’ absence wouldn’t exclude it from being native, with significant noise for reintroductions of animals extirpated for longer (for example, reintroduction of Tasmanian devils8,9 after 3000 years of extirpation10 – another topic deserving its own post some time). However, with suitable habitat shrinking in Kimberley1, there’s little point in transferring and releasing animals only for them to decline to extinction anyway, especially as zoo stock for this long-beaked echidna is nearly non-existent. The only possible evidence I could find looks a little.. unofficial.. but states there was at least one animal in Moscow Zoo until recently11. So hardly a successful breeding program. Taking animals from the wild to rehome would be rife with difficulty: catching the animals, proving that they’re healthy, transporting them, ensuring they could adapt to their new home, all while depleting the New Guinea population. And even if we assume there is, or was until recently, a wild population of western long-nosed echidnas in Australia, we can’t be sure they’re not a distinct subspecies without more evidence and samples. Ironically enough, releasing this echidna as an insurance population could actually endanger any population that might still exist as the subspecies mix and homogenate. Without more proof of wild animals there, reintroduction could threaten a putative population; with more proof, reintroduction is only more likely to threaten a population. In-situ conservation seems to be the only way to go for the western long-beaked echidna for now.

There has been a proposal to go looking for the fabled Kimberley population2. It sadly petered out, for reasons I can’t completely fathom. Perhaps there isn’t enough incentive to go chasing something with little evidence of its existence in the last century, perhaps there are worries finding another population would reduce interest in conserving the New Guinea animals. But as the western long-beaked echidna is in a critical state, it seems to be vitally important we know its true range to conserve it properly and, if there are more in Kimberley, to protect them and recognise a second echidna species living wild in Australia.

Referneces

1Helgen KM, Miguez RP, Kohen JL & Helgen LE. 2012. Twentieth century occurrence of the long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bruijnii in the Kimberley region of Australia, ZooKeys, 255, pp. 103-132

2Burton A. 2016. The echidna enigma, Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 14(3), p. 172

3Allen GM. 1912. Zaglossus. Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Ecology, 40, pp. 253-307

4Musser AM. 2003. Review of the monotreme fossil record and comparison of palaeontological and molecular data, Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 136(4), pp. 927-942

5Phillips MJ, Bennett TH & Lee MSY. 2009. Molecules, morphology, and ecology indicate a recent, amphibious ancestry for echidnas, PNaS, 106(40), pp. 17089-17094

6Murray P & Chaloupka G. 1984. The dreamtime animals: extinct megafauna in Arnhem Land rock art, Archaeology in Oceania, 19, pp. 105-116

7Leary T, Seri L, Flannery T, Wright D, Hamilton S, Helgen K, Singadan R, Menzies J, Allison A, James R, Aplin K, Salas L & Dickman C. 2016. Zaglossus bruijnii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T23179A21964204. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T23179A21964204.en

8Hunter DO, Britz T, Jones M & Letnic M. 2015. Reintroduction of Tasmanian devils to mainland Australia can restore top-down control in ecosystems where dingoes have been extirpated, Biological Conservation, 191, pp. 428-435

9Westaway MC, Price G, Miscamble T, McDonald J, Cramb J, Ringma J, Grün R, Jones D & Collard M. A Palaeontological perspective on the proposal to reintroduce Tasmanian devils to mainland Australia to suppress invasive predators, Biological Conservation, 232, pp. 187-193

10White LC & Austin JJ. 2017. Relict or reintroduction? Genetic population assignment of three Tasmanian devils (Sarcophilus harrisii) recovered on mainland Australia, Royal Society open science, 4: 170053

11Zoo Institutes. Long-nosed echidna. Available at: https://zooinstitutes.com/animals/long-nosed-echidna-1735/, accessed 16/02/2021

Pingback: The Fitoaty, Madagascar’s Shadow Cat – Novel Ecology