Cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) are small, stocky, white herons which have set themselves aside from other egrets, or really any other birds, by independently taking over most of the world in a matter of decades. This rapid expansion is natural. Sort of. They at least haven’t been introduced by people, taking the initiative to spread themselves across nearly every continent in less than two centuries (and they’ve had an ill-advised go at Antarctica, too), fitting themselves neatly into a niche which was once quite limited but is now ubiquitous thanks to yours truly: humankind. The key to this success lies in following the hoofprints of big herbivores and picking off whatever they kick up, a commensal feeding habit which isn’t wholly unique but not embraced so heavily by any other animal. This situation has some people scratching their heads, because how do we classify a species if we left the door open but they let themselves in? Are they naturalised? Introduced? Invasive? If they naturally expanded into unnatural habitat, is it a natural expansion or not?

Whatever you call it, the great emigration of the egrets is a fascinating case study for rapid species expansion, recorded in almost real time by ornithologists around the world.

Past

Cattle egrets are native to the northern coast of Africa and patches of Iberia, India across to Japan and south-east Asia, and to the Seychelles archipelago. These separate ranges define three subspecies: the western (B. i. ibis), eastern (B. i. coromandus) and Seychelles (B. i. seychellarum) cattle egrets; the former is sometimes split from the latter two as its own species. First described under the blanket heron genus Ardea, the cattle egret has since been given its odoiwn genus Bubulcus but is sometimes still lumped with other stocky, generally pale herons in Egretta or Ardeola. (For anyone confused, the English word ‘egret’ is just a catch-all term for white herons, like how ‘toads’ are just lumpy frogs or how ‘crabs’ are squashed lobsters).

Image: McDougall / Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service

Cattle egrets largely do their own thing away from their heron brethren, chasing grasshoppers, moths, lizards and other small animals from under the feet of large grazers. Though not absolutely tied to this lifestyle, cattle egrets find much more success with this technique than any other; every so often, however, they remember to be herons and traipse lakesides or riverbanks for crayfish, frogs, snakes or even occasional fish. They also nest in mixed heronries, pretending not to stand out, in mangroves or tree branches overhanging water.

Their herbivore-stalker attitude is quite specific and is perhaps what left the egrets with a fairly narrow range in Afro-Europe, though they were more widespread in Asia. They rely on high densities of slow-moving grazers in semi-arid short open grasslands, and there aren’t many places with this combination of climate, habitat and plentiful lumbering animals. Cattle egrets were actually more common in the last glacial period, because lower temperatures meant more global water locked in ice, so drier climates, suppressed forests and more open grassland. As we’re about to see, an ice age climate is not the only thing which can form these perfect conditions, and in the last few hundred years the cattle egret has found a new bastion called… cattle.

Present

So cattle egrets follow large, slow grazers around pecking at the small animals they disturb. Happily enough for the egrets, no one said those grazers have to be wild: in the Anthropocene, cattle are the world’s most abundant large herbivores. The expansion of grazing agriculture has opened up vast habitats for the egrets all across the world, giving them new opportunities in all directions. The birds flew in to find new pastures. That is, the pastures literally didn’t exist until the last couple of centuries. It’s free real estate!

Image: K Nagarjun / Flickr.com

The egret’s most famous escapade was a journey across the Atlantic Ocean, settling itself likely around Suriname and Guyana some time in the late 1800s or early 1900s. Sources differ but the first official records occurred between 1937 and the 1940s, with anecdotal sightings going back to before 1915 and even as far as 1877. Ornithologists at the time lamented that something fascinating was going on under their noses, but that they seemed to be missing it. The egrets made quick work of spreading out, to the southern US by the 1960s and Tierra del Fuego by 1977, by which point they’d covered as much American ground as climate would allow. To demonstrate the sheer rapidity of their range expansion, cattle egrets rocketed across the Gulf of Mexico’s north coast between 1955 and 1958: just 4 years! What’s more, a combination of written records and genetics show that, having landed in one of South America’s northern coasts, cattle egrets then invaded Brazil from the south! The authors of the study behind this finding suggest the egrets either hopped over or circumnavigated most of the enormous Amazon rainforest in a decade, though they fleetingly mention that the egrets may instead have simply colonised South America a second, separate time when they appeared in southern Brazil. Actually, it looks like cattle egrets are capable of crossing the Atlantic fairly regularly since they’re sometimes seen part-way along the trip and the American birds have suspiciously high genetic diversity for a single founding population. Looks like they were always ready to take the leap, they just didn’t have anywhere to land!

Now, in my researching I came across a pretty handy study from 1965 by an RH Lowe-McConnell. The whole thing is written from observations of a single roost in the Botanic Gardens of Georgetown, Guyana, so pinch of salt. But it serves as a useful record for shortly after the egret’s colonisation, wherein she recognises that nothing in South America really fills the cattle egret’s niche, so they faced very little competition. She also found that, although sharing heronries with native species, cattle egrets were first to roost and may have pushed out great white egrets which prefer their own space. She goes on to theorise that cattle egrets are only successful breeders when in large groups, and this is why they took a little while to spread into the farmlands erupting in South America since a whole flock of egrets would have to cross the ocean at once for the founding population to.. ahem… take off. As a final note, she mentions this interesting novel predator cascade, whereby native caiman were repressing (eating) Indian mongooses and so protecting the egrets from egg-eaters. Lowe-McConnell also includes a bit of snark at local kids in a very ecologist sort of way:

“….nests in exposed situations which could be watched were the most easily destroyed by predators (including small boys)”

and:

“The merits of lower nesting sites may include greater protection from…other elements (though they are more exposed to small-boy egg-thieves which are now a hazard)”.

Clearly she was having some trouble!

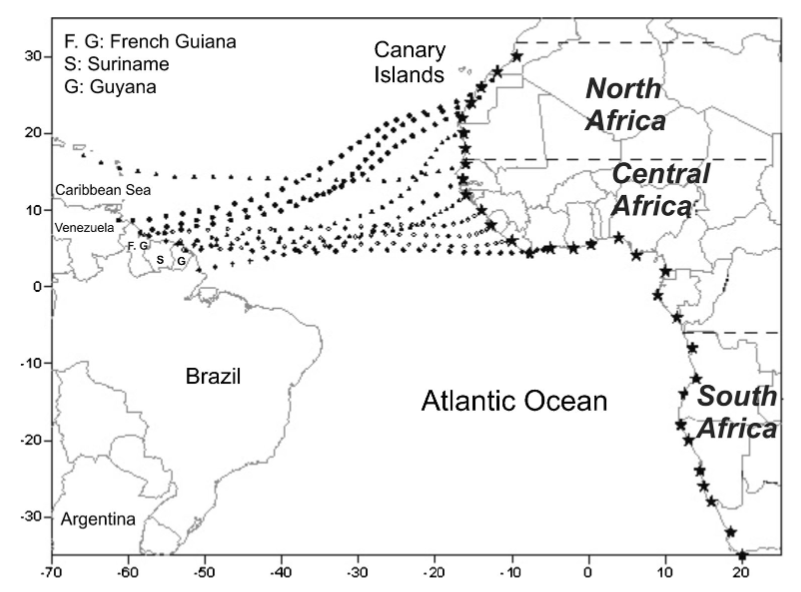

I want to talk about another study which definitely deserves its own paragraph. Massa et al (2014) used retroactive weather pattern modelling to recreate the likely pathway of the cattle egrets that first invaded the Americas. They used models of 150-year-old wind conditions to work out the most likely journey taken by the first colonising egrets! Isn’t that nuts? Using a window between 1871 and 1920 to generate their probabilities, they looked first at chance of arrival anywhere on the American east coast, then specified the region in northern South America where cattle egrets were first reported to have settled. They found that the egrets likely crossed from south-west Western Africa (in the authors’ central latitude band), and this was even more likely (85%) when they specified the egrets arrived in Guyana and Suriname. I had no idea biometeorology was a thing but here we are, recreating 150-year-old flight paths using the weather!

Image: Massa et al (2014)

Okay, so the American invasion of the cattle egrets is their most famous expansion, but it’s hardly the only one. Similar agricultural developments were opening up territory in far east Asia, south into Australia and even New Zealand. Although some birds were released in Kimberley, Western Australia, evidence points towards natural immigration in the early 20th Century, with birds subsequently colonising further south in the next 50 to 75 year to breed in New South Wales by the late 1970s and at some point reaching the south-west corner of Western Australia too. This expansion is really intriguing considering this is not only a separate population but a separate subspecies from the one which, right at the same time, stormed through the Americas! Wintering populations began to appear in Tasmania and New Zealand in the early 1960s, becoming regular migrants here in the late 1970s, and those which make the journey annually appear faithful to their favourite wintering sites. This is all bloody weird of course, because the birds are moving away from the equator for winter. Maddock (from whom I’m getting most of this Australasian info) suggests this might be for food availability, the birds enjoying a glut of earthworms in the wet winters of the south.

Even in the ‘Old World’, egrets are seeing expansion. Irrigation and denser cattle grazing is making the drier parts of Africa more hospitable to the egrets and they exploded across the continent in the 19th Century, reaching the Cape of Good Hope by the mid-to-late 1800s. Cattle egrets continue to move into the Sahara Desert with increased land usage. Unfortunately, most of the literature I could find about this African expansion is locked away in journals I can’t access. But it looks like Siegfried (1966) should be a good review of cattle egret spread and presence up to that time.

Cattle egrets are also spreading further into Europe, and the RSPB even bothers to list them as wintering in the UK and Ireland in low numbers. (Again, what’s up with this wintering away from the equator thing?) That said, my 2006 edition of Rob Hume and RSPB’s Birds of Britain and Europe tells me sternly they’re found in the Iberian peninsula and very southern France, only appearing as rare vagrants elsewhere in Europe. Maybe I need a new bird guide! I’ll take any excuse. Anyway, seeing as Europe has had dense grazing and substantial agriculture for thousands of years and the spread is uncharacteristically slow for the cattle egret, I’d say this looks more like a reaction to global warming than an embrace of new grazed meadow habitat.

Image: Miles Kitching / EcologyEvo

So, for the most part at least, cattle egrets have not been introduced by humans but have happily piled into human-made landscapes. Does this make them introduced? Invasive? Uh…hmm. Audubon Guides reports that the egrets may crowd out other herons from nest sites in the north of their American range but otherwise don’t seem to be invasive. This is a similar view to the one held by Lowe-McConnell, who seemed to find that competition for nest sites was stronger within species than between them. Though loud and a bit smelly in large numbers, the egrets are handy pest control, with a palette for grasshoppers and crickets, as well as ticks. Island ecosystems may be more vulnerable, such as in the Galapagos where they eat native lizards and could displace seabirds. Most authorities consider cattle egrets as invasive, although they are rarely high on the priority list.

Future

Chances are, the cattle egret’s range expansion will continue with the further sprawl of agriculture, especially in places where populations are rising fast and demand for grazed cattle increases. This will be aided by global warming, and as I’ve said we’re already seeing this have an effect entirely separate from the sudden ubiquity of cows. As a demonstration, by the time global temperatures rise past +3oC of warming, cattle egrets will be settling down in Boston, Toronto and Bismarck. Cattle egrets have been scouting out those few places where they don’t already exist, with sightings from Fiji and the South Pacific as well as (unbelievably) the Antarctic South Shetland Islands. Yes, a tropical heron species in Antarctic territory. That’s not to say they’ll move in any time soon – what birds have been sighted were malnourished corpses – but it’s nuts that they’re even down there and surviving for months at a time. I’ll also be curious to see if cattle egrets become regular breeders in their outlandish current wintering ranges, in western or central Europe, Tasmania and New Zealand.

Image: Michael McCarthy / Flickr.com

Of course this sort of thing gets me very excited for some fast-paced evolution. Think of it: witnessing the wide-scale speciation of a cosmopolitan anthropocentric bird as its newly-established populations splinter and become distinct… But I’ll stay realistic, because all these splinter groups aren’t going to suddenly speciate any time soon. Despite the expansion, east and west egret subspecies have remained separated by the Middle East as far as I know. But there is almost certainly gene flow still happening from Africa to the Americas even if wind directions mean the return journey might not happen so often. Within the Americas, movement seems to be quite free and cattle egrets are capable of migrating over 4000 kilometres, so they should hop up and down the supercontinent pretty happily. Maybe as much won’t happen in Australia though, or between the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan birds. And in a few hundred thousand years, perhaps we’ll see separate east and west species, broken up into a bunch of localised inland, insular, tropical, temperate, American, Australian, Antarctic(!) or other subspecies. I mean, we won’t see it, but something after us might. Maybe. And I enjoy that thought.

References

1Massa C, Doyle M & Fortunato RC. 2014. On how cattle egrets (Bubulcus ibis) spread to the Americas: meteorological tools to assess probable colonisation routes, International Journal of Biometeorology, 58, pp. 1879-1891 | Link

2Hubbs CI. 1968. Dispersal of cattle egret and little blue heron into northwestern Baja California, Mexico, The Condor, 70(1), pp. 92-93 | Link

3Downs WG. 1959. Little egret banded in Spain taken in Trinidad, The Auk, 76(2), pp. 241-242 | Link

4Cattle Egret, Audubon Society, https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/cattle-egret

5Davis. 1960. The spread of the cattle egret in the United States, The Auk, 77(4), pp. 421-424 | Link

6Lowe-McConnell RH. 1965. Biology of the immigrant cattle egret Ardeola ibis in Guyana, South America, Ibis, 109(2), pp. 168-179 | Link

7Line L. 1995. African egrets? Holy cow!, International Wildlife, 25(6), 00209112 | Link

8Moralez-Sila E & del Lama SN. 2014. Colonization of Brazil by the cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis) revealed by mitochondrial DNA, NeoBiota, 21, pp. 49-63 | Link

9Phillips RB, Wiedenfeld DA & Snell HL. 2012. Current status of alien vertebrates in the Galápagos Islands: invasion history, distribution and potential impacts, Biological Invasions, 14, pp. 461-480 | Link

10Bachir AS, Ferrah F, Barbraud C, Ceréghino R & Santoul F. 2011. The recent expansion of an avian invasive species (the Cattle Egret Ardea ibis) in Algeria, Journal of Arid Environments, 75(11), pp. 1232-1236 | Link

11Browder JA. 1973. Long-distance movements of cattle egrets, Bird-Banding, 44(3), pp. 158-170 | Link

12Congrains C, Carvalho AF, Miranda EA, Cumming GS, Henry DAW, Manu SA, Abalaka J, Rocha CD, Diop MS, Sá J, Monteiro H, Holbech LH, Gbogbo D & Del Lama SN. 2016. Genetic and paleomodelling evidence of the population expansion of the cattle egret Bubulcus ibis in Africa during the climatic oscillations of the Late Pleistocene, Journal of Avian Biology, 47(6), pp. 09088857 | Link

13Gassett JW, Folk TH, Alexy KJ, Miller KV, Chapman BR, Boyd FL & Hall DI. 2000. Food habits of cattle egrets on St Croix, US Virgin Islands, The Wilson Bulletin, 112(2), pp. 268-271 | Link

14McKilligan NG. A long term study of factors influencing the breeding success of the cattle egret in Australia, Colonial Waterbirds, 20(3), pp. 419-428 | Link

15Maddock M. 1990. Cattle egret: south to Tasmania and New Zealand for the winter, Notornis, 37(1), pp. 1-23 | Link

16Simpson K & Trusler P. 2010. Field Guide To The Birds Of Australia. 8th ed. Camberwell, Vic.: Viking (Penguin), p. 76

17RSPB. 2021. Bird facts: cattle egret. Accessed 24/01/2021 | Link

18Hume R & RSPB. 2006. Birds Of Britain And Europe. London: Dorling Kindersley, p. 46

19Silva MP, Coria NR, Favero M & Casaux RJ. 1994. New records of cattle egret Bubulcus ibis, blacknecked swan Cygnus melancorhyphus and whiterumped sandpiper Calidris fuscicollis from the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, Marine Ornithology, 23, pp. 65-66 | Link

20Siegreid SR. 1966. The status of the cattle egret in South Africa, with notes on the neighbouring territories, Ostrich, 37, pp. 157-169 | Link