Near the start of this month, researchers from Hungary (and one American) published a study in Genes in which they describe what was thought impossible. They had successfully cross-bred Russian sturgeon (Acipenser gueldenstaedii) with American paddlefish (Polyodon spatula), two species of fish from entirely different families. Why is this weird? Because with 180 million years of evolution between them, members of these groups should be far too different to produce offspring. And yet the researchers have 100 little hybrids swimming in their tanks that, going by most scientific understanding, just shouldn’t exist. The press has named them sturddlefish because, since they’re not true sturgeon nor paddlefish, what else can you call them?

The hybrids were not intentional creations. They were born as a control to a standard method called gynogenesis used to breed sterile female Russian sturgeons for caviar production. Sperm from another species, in this case American paddlefish, is damaged with radiation before it fuses with the eggs so that the male DNA degrades and the developing fish are all sterile females: perfect for caviar production. An undamaged control group was set aside, matching three sturgeon eggs with sperm from four paddlefish in five different combinations.

The scientists never expected hybridisation – sturgeons and paddlefish are just too different. But lo and behold, the eggs were fertilised and grew into full-size hybrid sturddlefish! In fact, fertilisation rates were over 85% for every combination and 49-68% of hybrids survived to a year old. Not bad for animals that were thought impossible.

Animals from different families producing offspring is very unusual because, taxonomically, that’s the difference between a human and a howler monkey or a cat and a badger. The two families of the order Acipenderiformes split over 180 million years ago, which the press likes to point out is three times older than the split between mice and humans, so there has been a lot of time for them to evolve differently to one another. The fact that they can still somehow breed is like discovering that two jigsaws made in different factories by different companies somehow fit together.

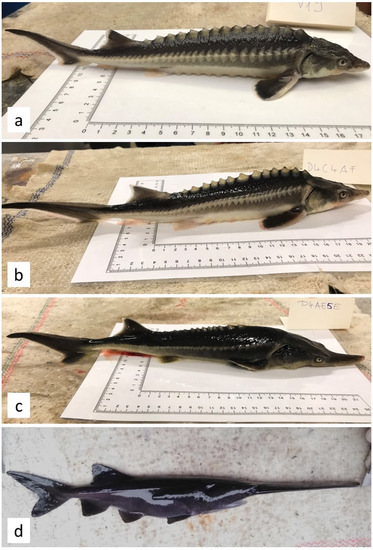

Microsatellite and principle component analysis showed that the hybrids come in a couple of different sorts: some of them carried two chromosome sets from the mother sturgeon and one from the father paddlefish (3n, or triploid), while others had four sturgeon sets and one paddlefish (5n, pentaploid). All of the hybrids are more sturgeon than they are paddlefish but the pentaploid hybrids are especially sturgeon-y. They are a little smoother and pointy-faced than the pure sturgeons, but not as Pinnochio-nosed as the triploid animals. This difference occurred because Russian sturgeons are tetraploid whilst Paddlefish are diploid, so most of the hybrids were triploid intermediates. In some hybrids, the sturgeon chromosome sets duplicated during early cell division, resulting in four sturgeon chromosome sets to one paddlefish set for a pentaploid five total that gave these hybrids even more of a sturgeon look. Interestingly, the total number of chromosomes (i.e. the size of each set) varied between individuals. The variation was in the microchromosomes, especially small DNA packages which can be lost without causing major issues. The hybrids also pose a unique opportunity to study inheritance and gene functioning.

How on Earth did this happen? The answer, according to the paper’s authors, lies in the slow rate of evolution in these fish groups. Despite the amount of time passed, their genotypes and phenotypes have been conserved to a surprising extent, meaning the two species are more similar than members of different animal families usually are. What’s more, those pentaploid hybrids and missing microchromosomes hint to the chromosome flexibility in these fish, also seen in reconstructions of both groups’ evolutionary histories. It seems the chromosome number can vary but the content of those chromosomes is very constant.

So are we witnessing the creation of a brand new species? Even a new, weird, hybrid family? Probably not. Hybrid animals like ligers and mules are usually sterile so its unlikely the sturddlefish lineage will go anywhere. Even if the fish could breed, the researchers have told the New York Times that they have no intention make any more of these hybrids, the parents of which would never meet in the wild, because of the risk of establishing a new invasive species in the area. However, they do hint in the original paper that since paddlefish are filter-feeders, the sturddlefish may have inherited a reduced reliance on invertebrate food which would make them cheaper and more sustainable to keep than pure sturgeons. With such a high breeding success rate, it’s also not impossible that private breeders might have a go at making their own ‘impossible’ fish.